- Home

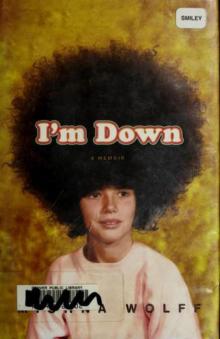

- Mishna Wolff

I'm Down Page 9

I'm Down Read online

Page 9

Dad said, “I almost lied about my age to go.”

“Serious?” her brother asked.

“Oh yeah,” Dad said. “A veteran in a wheelchair talked me out of it.”

Dominique’s brother shook his head and said, “It was the dumbest thing I ever did—get on that plane. I’m telling you, if you offered me a million dollars today to go back to Saigon, it’d still be no.”

I jumped in. “Especially since there’s no Saigon anymore.” We had been studying Southeast Asia in school and I was sure the grown-ups would think that was interesting. Nope, silence and stares. I backpedaled, “’Cause it’s not called Saigon anymore.” Still silence, still stares.

“What was that?” Dad asked in his scary voice.

It was then I realized I was talking way out of turn. And I practically whispered, “Ho Chi Minh City.”

“Why don’t you go on downstairs? The grown folks are talking.”

“Okay,” I said, and I slumped away, both embarrassed and unsure of how much trouble I was in. I headed to the basement where Dominique’s nephews were playing video games.

I sat down in the wood-paneled TV room with three of Dominique’s nephews and one niece, who ranged from my age up to fourteen. They were playing Nintendo, and I knew there wasn’t a snowball’s chance in hell of them giving me a turn. So I decided to watch. They were laughing and carrying on and having more fun than I had ever seen any kids milk out of a one-foot-by-six-inch machine. When Dwight the twelve-year-old died in Super Mario Brothers, he jumped up and acted out his death.

“Ya got me!” he said as his Mario died of a giant bullet.

And when Jordan the fourteen-year-old’s Luigi was killed by a fireball he jumped up and said, “I’m burnin’! I’m burnin’!” Meanwhile, Michaella, Dominique’s ten-year-old niece, laughed and laughed till I thought she was going to die of exhaustion.

“Daimon,” she said to her nine-year-old brother, who was also sitting out. “Do your Mario dance!” At which point this fearless nine-year-old did a little dance of ducking and jumping that he had worked out to the theme song on the video game. It was like a spontaneity convention. The whole scene was amazing to me and I could not have felt stiffer.

That’s when Daimon stopped dancing and asked, “What are you looking at?”

To which I responded, “I was just watching.” And I decided to head upstairs to see if Dad would take me back yet.

I crawled up the carpeted stairs because I thought that that was the way to handle sneaking back to Dad’s side. When I reached the top of the stairs and was about to head across the hallway to the dining room, I overheard a conversation going on around the dining room table.

Dominique was saying, “They are not gifted kids, unless gifted is another word for bad. That girl is b-a-d.” I knew she was talking about me.

Dominique’s brother added, “That girl is no more gifted than any of my kids, and she’s disrespectful, thinking she knows more than grown folks.”

I waited for Dad to jump in and defend me.

“Yeah,” Dominique said. “Where do they get off filling that girl’s head with all that crap about being smart? It’s just gonna mess her up when she gets to the real world thinking she’s better than other people.”

Dad finally jumped in, “Yeah, that school is full of uppity brats . . . ,” he said matter-of-factly. “But even before she went there, Mishna thought she was better than everyone. She’s just snotty like her mother. She’s her mother’s daughter. . . . Now Anora . . .” Dad got a pride in his voice. “Anora is my girl.”

I had to grab the railing of the stairs. I couldn’t breathe. Anora is his girl?

She hadn’t even tried! I was the capper. I learned dominoes. I hit Christopher Scott for him! How could I not be his girl?

I couldn’t even keep my head up and collapsed lengthwise on the plastic covered steps and slid back down them into the basement—enjoying the way each step felt hitting the back of my head and taking me out of my thoughts.

I certainly didn’t think I was better than anyone! In fact, I was pretty sure I was worse:

I was not as smart as my classmates.

I wasn’t cute like my sister.

I always said the wrong thing.

I couldn’t dance or rap or be spontaneous like Dominique’s nieces and nephews.

And I embarrassed Dad constantly.

I sucked and I knew it. I never asked to go to rich school, but as bratty and uppity as those kids might be, they were easier to please than Dad. So I hit my funny bone as hard as I could against the railing.

Five

THE JESSE OWENS STORY

WHATEVER RESISTANCE I still had to my school vanished in the stairwell of Dominique’s parents’ house. I was a changed girl. Not that Dad noticed—over the next week he was much too engaged with my sister’s newest undertaking. Anora and her best friend Maybelline had formed a six-year-old song-and-dance duo called the Sweet Beats. And Dad’s friend Reggie Dee was managing them—figuring he could do it as a side gig while he was growing his Amway business.

The Sweet Beats were conceived by Anora and Maybelline while they were taking African dance. They both studied at a studio called Ewajo, where Anora was the only white student—and didn’t seem to care. Ewajo was a Yoruba word from Nigeria and meant, “people, come dance.” Which made Ewajo a command, like “halt” or “pull my finger.” I really couldn’t figure out how exactly Ewajo led to the R & B-based Sweet Beats. She and Maybelline somehow managed to turn a dance relationship, fostered in traditional African pageantry and ceremony, into doing the running man and the cabbage patch in our shared room to their dope tunes like: “I’m Not Giving You My Digits” or “Somebody’s Triflin’.”

I didn’t go to Ewajo and wasn’t asked if I’d like to be included. I had already taken community center ballet when I was Anora’s age, which was like regular ballet but cheaper and oddly, more Asian. And after learning that tall people didn’t become prima ballerinas, I couldn’t really see the point of standing at a bar and pliéing till my eyes fell out next to the petite Vietnamese girl who, unlike me, would never have to play a prince or an animal. Maybe this was why I didn’t catch Sweet Beats fever like everyone else. Or maybe it was because the group jettisoned my sister from someone who sang and danced for fun into “a professional,” which was basically like asking her to never ever stop making noise. She was so empowered by her newfound status that she found the courage to keep me up at night—singing in bed.

“Let me sleep!” I would beg.

“I need to practice,” she would say. “I want to be on MTV.”

I would ball the pillows over my head and try to tune her out, but I had to admit, “Somebody’s Triflin’ ” was catchy. Which only made the whole affair more irritating.

My irritation with the Sweet Beats didn’t just come from being constantly annoyed—this was something more: I wanted nothing to do with the Sweet Beats fervor that was infecting everyone around me. Anora was Dad’s girl, so let her be. I was slowly finding that I wanted to act, I dunno . . . uppity.

A couple weeks later, we got to pick out our music instruments in school. If your parents signed a slip, you could participate in orchestra or band, and it was free. Not only that. They gave you a musical instrument—free. The word free caught Dad’s ear when I broached the subject over Monday night football. He kept looking at the TV, but I could tell by the way he stayed in his chair through the rest of the quarter that he was entertaining the idea of me playing an instrument. And during a time-out he looked up and said, “You should get a saxophone.”

“I dunno,” I said. “I was kind of thinking of something else.”

“Like what?” He asked.

Anything else, I thought. But what I said was, “I don’t know, something more classical.”

“You know . . . ,” he said, returning to the game. “You’re kind of too small to handle a tenor sax, otherwise that would be cool. I think alto sax is a good choice

for a girl.” Then he screamed at the TV. “Run, motherfucker! Run!”

I couldn’t handle the idea of playing sax—not in my house, not now that I knew how much I embarrassed Dad already. I could already see Dad’s shame at the dominoes table with his buddies—the sounds of me practicing my sax wafting in from the other room, and him blaming my lack of soul on my mother. Not that he could play any musical instrument, but he was a skilled air trumpet player, which made him an expert on all metal instruments.

The morning I was supposed to get my saxophone, Dad was in a hurry to get out the door. I presented the slip he was supposed to sign saying that I was taking home a musical instrument and if something happened to it, he would be responsible for it. He perused it for a second then made a face at the word responsible. He looked at the paper for a while, scratching his chin, and then slowly signed it.

He handed me back the pen, and said, “When you get home today I’ll play you some Charlie Parker . . . the Birdman!”

“Birdman. Birdman. Birdman,” my sister said.

“Okay,” I said, picking up my slip and putting it in my backpack. “Sounds great.”

“Oh yeah,” he said. “You don’t know what great is yet. But your dad’s gonna take you to school.”

“I want to hear the Birdman!” my sister screamed, crumpling in a heap on the floor.

“Take care of your sister,” Dad said.

Of course, at school the event of the day was music class. All day there had been chatter about getting our instruments, and once we were all actually in music class there was no controlling the excitement. We waited in line while Mrs. Hathaway, a fifty-year-old woman who dyed her short white hair purplish, took our slips and one by one gave us the instrument we wanted. More than anything people were walking away with violins. Christopher passed me with a violin and a bummed out look on his face.

“Hey,” I said. “You’re playing violin?”

“Yeah,” he said. “I wanted to play sax, but my dumb parents are making me.” He looked really disappointed, and at that moment I thought about bragging about how Dad actually wanted me to play saxophone. But instead I put on my most disappointed face, shuffled my feet and said, “Yeah, my parents are making me play violin, too.”

Christopher gave me a sympathetic look and a smile. And I had never been more interested in the violin.

“God,” I said. “Why are parents so dumb?”

“Exactly,” Christopher said. “It’s like they have to be involved in everything, all the time.”

“I know!” I said, trying to sound like I was gonna barf. “It’s like, I’m my own person, right?”

That afternoon, as I walked in the house with the beat-up violin case in my hand. I decided to lie and tell Dad they had run out of saxes. He stood at the kitchen counter, shirtless with a basketball in his hand, and went through a litany of other instruments I should have chosen while trying to spin the ball on his finger, “Trumpet, trombone, clarinet . . . tenor fucking sax!”

I shrugged, and he dashed into the living room,

“Follow me!” he said, throwing the ball at me for me to catch, and not noticing it bounce down the front of my chest.

“I’m gonna teach you a little something about jazz.” He was already leafing furiously through a stack of cassettes.

“So, Mishna,” he said. “What about you get on the wait list or something for a sax tomorrow?”

But I knew I wasn’t giving my violin back. No matter how many times he played me John Coltrane.

“I think maybe we should stick with this for a year and see how things go,” I said. “Let’s just try it.”

“Fine,” he finally said. “Have it your way.”

Which was his way of saying, “I will get you back soon . . . and when you least expect it. . . .”

The next day, I walked my new violin home from school again feeling proud—and free. I had no idea what to do with it yet, but it felt so good to have something so wonderful and foreign in my hand. It was a cheap violin that had been abused by dozens of students’ greasy fingers, but as I walked with it into the corner store to buy a ten-cent pack of Now and Laters, I imagined it made me look both smarter, richer, and like my parents were really overbearing. I didn’t even mind when an older black woman in a Monte Carlo pulled over beside me outside and asked if I was lost.

But the second I walked in the door, I could tell by Dad’s face he had an announcement. He was wearing that look he always wore when he had just made a decision that involved all of us. His face said, “I have great news—we are starting a skunk farm!”

I set my violin down on the counter just as he said, “I have great news!” I set my bag down. “I signed you up to run track!” If he had finished the thought, he would have said, “You’ll be the only white person on the team, and probably the slowest.”

But he didn’t. He looked at me excitedly until I said flatly, “That’s great, Dad.”

He got more animated and started to move his hands around as he said, “You gotta be more physical, too, you know. You go to school for your head”—he pointed to his head—“but that ain’t everything, you know. You need to be well rounded.” I looked at him blankly as he traced a circle with his hands to represent “well rounded.” But I knew now what well rounded meant. It meant, “We need to balance all that uppity white shit out, because you’re embarrassing me.”

______

When I arrived at my first practice at CDAC, Central District Athletic Club, it felt like I had accidentally walked into gladiator training. Everyone was huge and strong, and they looked like grown-up Olympic athletes. I had never seen twelve-year-old boys whose muscles were cut like Ben Johnson, or fourteen-year-old girls who moved like Jackie Joyner-Kersee.

As I walked across the field, holding my father’s hand, I saw a girl my age take a long jump. She raced to the line and sailed into the air, pumping her feet until the final moment when she thrust them out in front of her to grab those extra inches on the landing. She smiled like crazy as she picked herself up from her jump, and ran to where the rest of the team was running laps. And as she folded back in with the group, a teammate laughed and slapped her back almost as if to say, “You just can’t get enough long jumping, can you?”

In the middle of the field a line of boys were pole vaulting, something I had never seen before, and reminded me of Evel Knievel. I watched amazed as they flew through the air and then landed softly like cats. It was like they were bionic.

Everywhere I looked huge majestic dark bodies jumped and sped through practice with perfect skill and grace, chests out, legs pumping. I was witnessing physical excellence for the first time—gods in training. I was totally fucked.

And then I saw Zwena. Zwena was like this wonderful oddity on the team. I spotted her loping on the other side of the field wearing her glasses with an elastic head strap and carrying an inhaler in her shorts pocket. She ignored all the coaches yelling and smiled as she remained completely in her own world, oblivious of the people dashing by her and the fact that we were supposed to be competitive. There was hope.

______

The ages on the team ranged from seven to seventeen so I was put with the younger kids because I was nine. The few older kids, from what I could tell, were stars and got their own personal workout from the coach. Not that we didn’t all share the same track, which meant if one of these stars was coming up behind you, they had the right of way. The muscular person moving at the speed of sound always has the right of way.

After school I immediately left my new school friends who were really starting to like me, and took a bus to a field full of neighborhood kids who would jump on my dead body if they thought it would add spring to their high jump. I know that because I slowed once on the track and didn’t move out of the way quick enough for twelve-year-old Jada to lap me. She body-slammed me to the ground and then, angry that her stride had been broken, pointed to her spikes and saying, “Next time, I’ll stomp your face and not think t

wice about it.”

Running at CDAC also seemed to have some weird association to a man named Jesse Owens. Jesse Owens was the meet we sponsored and the guy on the medals. Zwena didn’t know who he was, but I thought we might be his team. We both had the sense not to ask the coach who Jesse Owens was. My coach was a six-foot-three bulldog with a whistle. And I worried if I asked him who Jesse Owens was, he’d say, “You’re on his team, dummy!” Then he would call Jesse Owens over and Jesse Owens would karate chop me in the neck. Or worse, kick me off the team, which I would have no way of explaining to Dad.

One night, Dad came to watch the last half of my workout. I had really tried to hold my own on the field so he would be happy, and as we left practice I was truly exhausted. We got in the car and were at least five blocks from the track. “Dad, who is Jesse Owens?”

Dad looked at me quizzically and said, “I never told you the Jesse Owens story?” Then he scratched his chin, “Okay,” he said. “Jesse Owens was a black man who won the Olympics, but he took a lot of shit for being black. I mean a lot of shit.”

I tried to imagine what that looked like. I said, “Did people throw rocks at him?”

“Well,” Dad said. “I don’t know all that, but he had to eat at different restaurants than the other folks on the team, and he couldn’t do all the stuff white athletes did. And he really pissed off Hitler.”

I was confused. “I thought Hitler hated Jews.”

Dad said, “Oh, he hated black people, too, a lot. Hitler hated all people who were different. And when Jesse Owens won all the Olympic races, it was in Germany, and Hitler got so mad he went off.”

“That must have been scary,” I said. “I mean Hitler is already scary. Was Jesse Owens afraid that Hitler would kill him in an oven?”

I'm Down

I'm Down