- Home

- Mishna Wolff

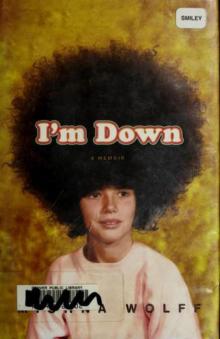

I'm Down

I'm Down Read online

I’m Down

I’m Down

A Memoir

MISHNA WOLFF

St. Martin’s Press

New York

I’M DOWN. Copyright © 2009 by Mishna Wolff.

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. For information address St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

www.stmartins.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wolff, Mishna.

I’m down / Mishna Wolff.—1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-1-4299-8290-0

1. Wolff, Mishna—Childhood and youth. 2. Wolff, Mishna—Family. 3. African American neighborhoods—Washington (State) 4. Comedians—United States—Biography. 5. Models (Persons)—United States—Biography. I. Title.

PN2287.W55A3 2009

792.702'8092—dc22

[B] 2008046317

First Edition: June 2009

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my mom and dad, who gave me the best childhood I would never have been smart enough to ask for.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

OKAY, THIS IS IMPOSSIBLE. I have received so much time, guidance, effort, and encouragement on this book. Let me start by thanking all the amazing people at St. Martin’s: Lisa Senz, Sarah Goldstein, Sally Richardson, John Murphy, Dori Wein-traub, Stephen Lee, and everyone else who did the hell out of their jobs. And most important, Rose Hilliard, my fantastic editor, who brought so much to this book and just gets it.

Thank you, Erin Hosier, the best agent a girl could have, seriously. Sarah Thyre, for doing me a favor for no good reason and expecting nothing in return. My sister and best friend Anora, whom I am so proud of. The writers who pulled out a chair for me at the table: Jill Soloway, Maggie Rowe, Darcy Cosper, Josh Olson, and Claudia Lonow—thank you. The Fox family, especially Lauren Fox, my friend through all seasons. Virgina Scott, for your help with this story. Frank Hannah, a mentor who deserves a whole page. Hillary Malloy and the Malloy family, for filling a lot of seats and feeding me so often. Ira Sacheroff, my very funny and even-tempered stepfather. My stepbrother Sam, he-he. UCB Theater, Caliber Media, Eric King, Pat Healy, Jaclyn Lafer, Richard Potter, and the Doners; Linda, my stepmother, who makes life better. Lauren Francis—I couldn’t make it without you. Mrs. Romano, my seventh-and eighth-grade English teacher, who taught me about irony right when I needed it. Marc Maron, thank you for the risks you took and everything you shared with me. Lorca Cohen, you are truly a great friend who gave me a sanctuary to write in when my world got too chaotic. And thank you, thank you, thank you, Jeremy Doner, the most amazing man in the whole wide world. I promise I will make you so happy.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

EVENTS IN THIS BOOK may be out of sequence, a few minor characters are composites of more than one person, many conversations were re-created and names have been changed.

This book is from my perspective as I was growing up. I honored what I thought was true at that age, rather than what I might know to be true now. My memory is limited to what it is, and I didn’t always have all the information as a child. Others might tell it differently.

I claim none of this as gospel. That being said, most of this stuff is totally true.

I’m Down

Contents

Prologue

One: I’m in A Cappin’ Mood

Two: Ten-Foot Drop

Three: A Lesson-Learning Machine

Four: Dominique and More Lies

Five: The Jesse Owens Story

Six: Value Village

Seven: Are you Stupid?

Eight: Here and Now

Nine: Duck-Butt

Ten: Flagrant Foul

Eleven: Extracurricular

Twelve: The Family Racist

Thirteen: What’s the Matter with White People?

Fourteen: The Lake

Author Q & A

A Reading Group Guide

PROLOGUE

I AM WHITE. My parents, both white. My sister had the same mother and father as me—all of us completely white. White Americans of European ancestry. White, white, white, white, white, white, white, white. I think it’s important to make this clear, because when I describe my childhood to people: the years of moving from one black Baptist church to the next, the all-black basketball teams, the hours having my hair painfully braided into cornrows, often their response is, “So . . . who in your family was black?” No one. All white.

However, my dad, John Wolff, or as the guys in the neighborhood called him, “Wolfy,” truly believed he was a black man. He strutted around with a short perm, a Cosby-esqe sweater, gold chains, and a Kangol—telling jokes like Redd Foxx, and giving advice like Jesse Jackson. He walked like a black man, he talked like a black man, and he played sports like a black man. You couldn’t tell my father he was white. Believe me, I tried. It wasn’t an identity crisis; it’s who he was. He was from “the neighborhood”—our neighborhood.

We lived in an area of south Seattle called the Rainier Valley that your average white person, at the time, wouldn’t have gone to without a good reason. Not that there weren’t plenty of reasons to visit the Rainier Valley—there were. Right off M. L. King Jr. Way, I lived near the Langston Hughes Auditorium, not far from the Medgar Evers pool, close to the Douglass-Truth Library, down the street from the Quincy Jones Auditorium, which incidentally, was in the high school Jimi Hendrix went to. On the literary tip, Iceberg Slim had run a gang of hoes not far from where we lived.

But there were virtually no whites. There were the occasional middle-class white hippies who moved onto our street to escape bougie-ness, but they usually moved away when they had kids. And my dad always wound up hating them. Sooner or later they’d “be showing off” by throwing around their bachelor’s degrees or fixing their roofs, and we’d be banned from any interaction with them. Even before it was hip, Dad was “keepin’ it real.”

He’d moved to our neighborhood as a child in the early sixties, back when it was a white and Asian neighborhood. That was before school busing programs, when middle-class white people started moving out of the cities and into the suburbs, because, “you know.” My grandparents were too cheap to be racist. You don’t sell when the market is down. And as the neighborhood got blacker—so did my dad. He was in high school when he started to help the Black Panthers with the breakfast program. He played sports and he made his friends. They were the brothers and he was cool.

But after a quarter of college football failed to make him a star, my dad reinvented himself as a hippie and ventured east to Putney, Vermont. He grew his hair long, wore leather pants, and roamed the halls of higher education selling weed. It was here that he met my mom. She was smart, pretty, socially conscious, and super needy. And when my dad talked about civil rights, she assumed he was a feminist. She immediately quit school and moved to Maine with him to live in the woods with no electricity and no running water. He had that effect on women.

They did the “back to nature” thing for a while, but once my mom had me, my dad convinced her to move into the house that he grew up in. My grandparents were finally moving to a better neighborhood. And eventually my mom agreed: women like free houses. But once my dad was back on his block, he began to change—or rather change back.

He cut off his long hair and got a short perm, he became obsessed with his shoes, and he bought us an African drum coffee table, and one of those high-backed wicker chairs—you know, the ones you always see Huey Newton in. And he was invited by all his friends from high school to join the Esquire Club, an all-black men’s club. Within a year the man my mom had married had shed his crunchy granola skin, exposing a bona fide soul brother—and they teetered on the brink of divorce.

Meanwhile my litt

le sister, who was born in the Rainier Valley, took after my dad. She seemed to pop right out of the womb and into a dance troupe. She found so much love and approval in the black community, you’d think she’d invented beatboxing (see Doug E. Fresh).

So while my mom was busy planning her escape, my sister and father were cohorts—completely integrated into the community we lived in. And then there was me—the honky. I’m not saying that to be provocative or put myself down.

I was a honky. I couldn’t dance. I couldn’t sing. I couldn’t double Dutch—the dueling jump ropes scared me. I didn’t have great stories that started with “We was at . . .” and ended with “. . . I told her not to make me take my earrings off!”

Honestly, being a honky was A-OK with me. I wished my whole family were honkies. Big honkies! I wished we were the cover family for Honky Weekly. If I could have picked my family, they would have been honky professors that sat around in honky-assed tweed jackets reading the paper, stopping occasionally to say honky things about what was going on in China and how brilliant I was. They would talk in gentle honky voices and when they made a chicken they would THROW OUT THE GIZZARDS.

Instead I got my dad, sitting around playing dominoes with four large black men, who were all apparently my uncle, and who agreed that the only way to discuss affirmative action was—at the top of your lungs. They also thought kids were beer-fetchers crossed with remote controls and that there was something seriously wrong with my rhythm. I had a rhythm problem. This was not acceptable to my father, and so he began his crusade to make me “down.”

I remember it starting shortly after my sixth birthday. Without looking up from his dominoes game, he said to me, “You need to stop tryin’ to hang out with grown folk and get out and play with the neighborhood kids.” The four learned black men he played with sat at the dining room table nodding in agreement, but I wasn’t thrilled with the idea. I didn’t really know the neighborhood kids, but they all hung out on the end of the block, being bigger than me and knowing each other really well. What I was a fan of was hanging out with my daddy. Mom drove a city bus and Dad took care of me and my little sister, Anora, during the day. Sometimes he would have a job doing construction, and we would go hammer nails and stuff until someone got hurt. But usually he was entertaining these four guys from the neighborhood: Reggie Dee, Eldridge, Big Lyman, and Delroy. And I just didn’t get why he wouldn’t want me there, too—I was fun.

My first birthday.

My dad put his dominoes in order as he continued, “You know what you need to do?”

I had a feeling he was gonna tell me.

“You need to get out and make friends with the sisters.”

“You mean the girls out front of Latifa’s house?”

My dad nodded.

“Why?” I asked.

“You may need those girls someday, and . . . your neighborhood is where you live.”

“What do I do?”

“Just go introduce yourself,” he said. Then, waving his hands around, he added, “But not like you’re scared . . . like you’re doing them a favor.” I knew this had something to do with being cool, but I was scared and I didn’t see how I was doing anyone a favor.

“Those girls out there would be lucky to have you hangin’ with them,” Reggie Dee said.

“How come?” I asked. I liked Reggie.

“Well . . . ,” Reggie said, thinking.

“I’m smart,” I said. “Pretty smart for six.”

“Yeah,” Reggie said apprehensively. “But that’s not something you want to brag about.”

“Oh.” I didn’t get popularity at all. “Then what do I have?”

“Well . . . ,” my dad said. “You’re my daughter, for one. That’s one thing right there.” I waited for “two,” but he just looked angry that I was still there.

I walked out of the house toward the corner, where I saw a group of kids. The clear leader of the group was a chubby girl we called Nay-Nay. She had her honey-colored thighs shoved into a pair of Day-Glo bicycle shorts two sizes too small, and her fat piggy toes peeked out of a pair of matching plastic jellies. Jellies were a plastic ballet-style shoe that was popular in the neighborhood, but my mom wouldn’t let me have them, because she said they were bad for my high arches.

“Hi,” I said. “I’m Mishna. I live up the street. Do you want to be my friend?” Awful—I didn’t say it as though I was doing them a favor. I said it like I was scared.

Nay-Nay looked me up and down and then said, “Do you have any Barbies?”

“Sure,” I said. Then asked, “What’s a Barbie?”

Everyone looked at me like I was on crack, and Nay-Nay condescended, “Barbie is a doll. Do you have any Barbies?”

“Yes!” I said defiantly. “I do!”

“Well, get them . . . and you can hang out.” Nay-Nay said, putting her hand on her hip and blocking me from addressing anyone else in her group. But I stupidly stood there, not realizing that the conversation was over. I didn’t exist until I had that doll. Nay-Nay smacked her lips.

“Oh,” I said nonchalantly. “I’ll go get my Barbie.” And crept away.

I tore through the house past the dominoes game and into my room and began rifling through my dolls. I set them all on the bed in order to pick which of them, if any, was a Barbie doll. It was hard for me to tell what any brand-name toys were, because my mom didn’t let me watch commercial television. She said it rotted my brain, but I half suspected it was because not seeing commercials made it easier to be poor.

Making a quick and instinctual decision, I grabbed my favorite doll to bring back to the girls, which was Tommy, a stuffed turtle that someone had made for me. I tucked him carefully under my arm being very mindful of his head, because that’s where turtles are most vulnerable. And I hurried back upstairs—scurrying past my dad, who was in a shouting match with Lyman over whether or not he was cheating, and back out the front door. I didn’t know if I had the right doll, but I was carrying the best doll I owned, and I was pretty sure that everyone would be impressed with my hot-shit turtle.

The neighborhood kids were all standing in front of Latifa’s house fully into some sort of Barbie orgy. Hot, wild, Barbie-on-Barbie action, complete with sound effects like, “uh, uh, uh.” And besides discovering lesbianism, I found that what I was holding could not have been further from a Barbie.

“What’s that, whitey?” Nay-Nay asked, pointing to my doll.

“Tommy,” I said. “He’s a turtle.”

“You thought you could bring your broke-ass turtle down here to play Barbies?”

I shrugged.

And with that, Nay-Nay began cackling in a way that quickly caught on with the rest of the group. I just stood on the corner holding Tommy the Turtle as five black girls holding plastic white women laughed at my stupidity.

I was desperate and argued, “Mine’s a Barbie doll, too. . . . It’s just a different kind of Barbie!”

To which Latifa, a girl a year older than me, exclaimed, “That ain’t no Barbie doll! That’s something out of the Goodwill goodie box!” And when I didn’t walk away, Nay-Nay called me whitey again and gave me an embarrassing little shove in the direction of my house.

I marched back into the house and straight up to my mom, who had just gotten home from work. She was still in her work uniform, snacking on cheese and crackers at the kitchen counter, wearing her usual after-work expression of tired mixed with worry and coffee. She was deep in her cheddar and Ak-Mak, and looked surprised when I pounded the counter next to her and exclaimed, “Mom, I need a Barbie!”

“What about Tommy?” she asked, gesturing in the direction of my turtle. I threw Tommy on the ground.

“What about him?” I asked in a tone I hoped Dad didn’t overhear.

“You know, now you’ll never make turtle mother of the year.”

“I don’t care about my dumb turtle anymore!”

That got her attention. My mom turned to me and shook her head almost as if she kn

ew this day had been coming and said in a calm and sincere voice, “Honey, oppressed people of the world make Barbie so a big corporation can get rich. Now, is it really worth that kind of karma for a doll?”

My mother, father, and baby me—looking skeptical.

I tried to respond. “Um,” I said. “Well . . .” But I knew I couldn’t argue with karma and oppressed people in the Philippines.

A few days later, I walked out of the front door as my dad was putting the finishing touches on a tire swing in the front yard. “What’s that?” I asked.

He finished his knot and said, “Tire swing. I thought it would bring some other kids over here to play with you.” He added, “You’ll see. This’ll be the spot.”

“You think this will help me make friends?” I asked.

“Hells yeah,” my dad said. And then pointing to the swing, asked, “Who wouldn’t want to be on that swing?”

I guessed me was the answer, because that swing scared me. But my dad really knew about this stuff. So even though that swing just looked like something that was too high off the ground and not really clean clean, I knew its secret would reveal itself. And, sure enough, before my dad was done testing out his knot, Latifa had come over.

“So,” I said, looking awkwardly at Latifa. “You wanna go first?”

“Okay,” she said, and got on the swing. She swung for a little bit and then helped hoist me up and pushed for a while. And I was surprised to find that hanging out with Latifa when she was away from Nay-Nay was pretty nice. I also learned that her favorite word was daaang! She started every sentence with it. “Daaang, you sure have some nappy hair.” Or, “Daaang, why your parents dress you like a boy?” Or, “Daaang, you don’t got no booty at all!”

I'm Down

I'm Down