- Home

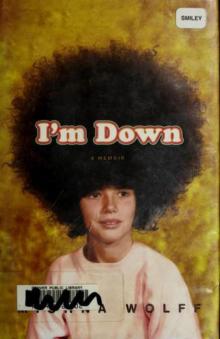

- Mishna Wolff

I'm Down Page 10

I'm Down Read online

Page 10

By now, my father had zoned out and he muttered, “Definitely.”

I looked at Dad proudly. I bet Kirsten’s father “the professor” didn’t know as much as Dad did about Jesse Owens. I was always amazed how much he knew about social injustice. I remembered when we had Dad’s friend Carl living with us for a while, who I hated until Dad explained to me that I didn’t know what it was like to be black and out of work. Then Carl stole our TV, but Dad didn’t get mad, he just said, “If Carl took that beat-up old TV, the joke’s, on him.”

I looked at the road and noticed we were driving past the turnoff for the house. “Dad, where are we going?”

He snapped back to attention and said, “Oh. We gotta get your sister from rehearsal.”

“What rehearsal?” I asked.

Dad looked at me like I was retarded. “The Sweet Beats.”

I didn’t realize we were taking them that seriously.

I had a lot of homework, plus we had seating tests for orchestra the next day, so I had to practice my violin. I asked Dad, “Dad can you just drop me home? It’s pretty much on the way and I have a lot of work for school.”

“You can hang out for a little bit. We have to support your sister’s endeavors, too.”

When we got to Maybelline’s house, I saw Reggie Dee’s car parked out front—so he was really managing them. Maybelline’s mom, Candy, was at work. We walked in to find the Sweet Beats hard at work in the little TV room while Maybelline’s socially awkward older half-brother, Carlos, holed up in his bedroom in silent protest. Reggie was sitting on the couch with a beer half watching the girls, who were in front of a mirror doing a dance routine that involved twirling an invisible hula hoop to Salt-N-Pepa.

I watched for a minute, trying to understand if there was some sort of order to what they were doing, but there didn’t appear to be any real throughline. Anora would do the running man, and Maybelline would follow. Then Maybelline would shake her butt and Anora would copy her. It was like dance class in the amnesia ward. I turned to see what Dad thought of all this, but he already had a beer open and was stretched out on the couch next to Reggie, like he lived there. The song ended and Maybelline asked, “What now, Uncle Reggie?”

Reggie looked up from the conversation he was having with Dad about the Raiders defensive line and said, “Um . . . just do it again.”

Two hours later, we were still there. Sweet Beats practice had dissolved into Anora and Maybelline in Maybelline’s room playing with her hair stuff. And Dad and Reggie were still on the couch, only now the game was on. Candy, Maybelline’s mom, was nowhere in sight and I was nowhere closer to getting my homework done or learning the stuff I was supposed to learn on my violin for seat assignments for orchestra.

“Dad . . . ,” I asked. “Are we close to leaving?”

I used my quiet voice, hoping he would magically hear me. He didn’t. He just continued looking straight ahead, lost in the TV.

“Dad . . . ,” I repeated, whining a little.

“What?”

“Dad, I have a lot of homework to do. And I have to practice my violin.”

“So,” Dad said, “no one’s stopping you. Do what you gotta do.”

“But—”

“Oh, stop,” Dad said. “Everyone’s having a good time. Just get your stuff and do your homework.”

I stomped out to the car and got my violin and schoolbag—seething. Every step through the dirt yard was an angry thought. What the hell . . . why couldn’t he just drop me home? Sweet Beats, my ass! I have very important things to do!

I wound up sitting on the kitchen floor and finishing my homework. It was clean enough for a girl who just ate dirt at track practice, but not as clean as a chair. Every now and then Dad would come in to grab a beer.

He looked at me with my books spread around me on the floor. “I guess I’m supposed to feel sorry for you, wif’ your little show! You look like a goddamn orphan!”

It didn’t take me long to finish my homework, but practicing for the seating in orchestra was gonna be a little more difficult. I walked back into the TV room where the game was over and, once again, the Sweet Beats were rehearsing. “Push It” was playing for the fifteenth time that night, and Reggie and Dad were smiling and laughing. Dad got up off the couch and started shaking his hips to the music.

“Let me show you girls a thing or two,” he said, doing an exaggerated version of what Anora and Maybelline had been doing.

“Dad,” I said. “I really need to practice. I need to go home.”

“Practice in the kitchen,” Dad said, moving into the chicken dance. “You do every other goddamn thing in there.”

“But,” I asked timidly, “when are we leaving?”

Dad stopped dancing and looked at me like I was the world’s biggest buzz kill. “You better stop your whining. . . . You just do what you need to do. We’ll leave when I’m ready to leave.” That was his final word.

I started to unpack my violin, saying to myself as I set up, “Fine! If he wants me playing my violin here for the whole house full of people, violin he shall get!” I put the resin on my bow, set up my music on the counter and put my chin in the chin rest—Salt-N-Pepa still blaring in the background. I lifted my bow. I put my bow down. I lifted it again, and squeaked out a very quiet note. I put down my bow again. I tried to play the piece very quietly. It sounded like shit. I worried that Dad and Reggie heard it and were making fun of me in the living room. I popped my head in the living room—nope, still dancing. But I couldn’t take any more chances. One day I would be a real violinist and I would play loud and well and fill a house with sounds so beautiful that everyone would stop what they were doing and listen. Today was not that day.

I packed everything up and sat next to Reggie on the couch with my arms crossed where I remained until ten thirty when Candy came home and we finally left.

______

The next day at seating tests for orchestra I ate it. I walked into the little room where Mrs. Hathaway auditioned us, and forgot the piece I barely knew to begin with. Mrs. Hathaway just sat there with a pen and notebook writing furiously with an angry face. When I finished she looked at me over her glasses and said, “Mishna, that was terrible.” Mrs. Hathaway was one of those old-school teachers who didn’t know that she was supposed to coddle my developing self-esteem. “Really . . . just one of the worst performances I have ever seen. I don’t know why you are wasting my time.” She stuck out her bottom lip and blew her bangs off her forehead. “You know, a lot of these kids have been playing since they were five. If you want to participate, you have to really apply yourself.” At the end of class, she put out the seat assignments. I was last chair, last violin. And someone was gonna pay for it.

At track practice I was too angry to run. I couldn’t find it in me to put one foot in front of the other. I took a lap, and I was done. But I couldn’t leave. I had to find a way to make it look like I was working out without actually working out. I began to sort of move around the various events on the field in a way that made it look as though I had just finished up that particular event. I moseyed away from the long jump brushing sand off my shorts, before making my way to the pole vault, which I left rubbing my sore pole-vaulting arms. This was working so well that I hid under the bleachers for the rest of practice and either nobody noticed, or nobody cared. Either way it felt great to completely play hooky from track practice.

As the weeks went by, I got lazier and lazier. My only real goal became to escape notice. I was almost a ghost on the team. I even began to think I had the same powers to disappear in plain view that I had had at GSCC. When I wasn’t doing that, I just ran with Zwena and we’d keep up a pace that was comfortable to have a conversation at.

“How’s it going at smarty school?” she’d ask.

“I feel pretty much like the weirdest person there all the time,” I’d say. “How’s it going at private school?”

“Rich and white,” she’d say, but always adding, “But I li

ke my classes.”

I was surprised when one day when we were walk-running and I asked, “I guess your dad pretty much made you run, huh?” And Zwena told me he hadn’t at all. She’d wanted to run and she thought it was fun. I just looked at her for the next lap, baffled. I couldn’t figure out why she would want to do anything that she wasn’t immediately great at.

Zwena and I had a good thing going, and then Dad reappeared at practice. He started by marching over to the head coach and having a long conversation with him. I could tell by the way they were looking at me from across the field that I was not as invisible as I had thought. From then on Dad came to every practice and coached from the sidelines. He even took to coaching Zwena, too, and suddenly she didn’t think running was so fun.

“Mishna,” he’d scream, “you still got half an hour left of practice—hit that like you mean it.”

I’d roll my eyes at Zwena just in time to hear Dad tell her, “Zwena. You, too! Stop actin’ like you’re dying. Neither of you two is gonna die from some wind sprints.” And the more involved Dad got in track, the more exhausted just thinking about a track made me.

Every weekend for the rest of the season Dad dragged me and Zwena to track meets, and I tried to invent injuries in the car on the way. I wasn’t that good a runner, I could imagine I was injured so deeply, I could actually cause swelling. I would limp into the car at 7:00 A.M. on a Saturday morning whining, “Daaaaaad, my calf has a cramp . . . and on top of that, I think I twisted my knee coming down the steps. It might be my rotator cap.” But Dad would just grin and say, “When we get to the meet you can take a few laps—walk it off.”

One night I was in my bedroom practicing my violin. My sister had made her usual show of running out of our bedroom with her hands over her ears.

“What?” I asked. “Am I that bad?”

“I just have to go,” she said. “That kind of music messes with my rhythm.”

“Fine,” I said. “I’ll be done in a half an hour. Just listen to one side of your Salt-N-Pepa tape.”

“Ooh, good idea,” she said, and slammed the cheap pressboard door on the way out.

I had been practicing for thirty—or five—minutes when Dad walked in. I nervously stopped playing.

“I didn’t kick Anora out,” I said. “She left on her own.”

But Dad just looked at me for a moment before saying, “I think at the next meet we’re gonna enter you in the four-hundred-yard dash.”

“That’s a long way,” I said.

“It’s nothing,” Dad said. “And I really think that it’s the right distance for ya.”

But I was pissed. At the time I was doing fifties and hundreds, and four hundred yards—that was like miles.

“But, Dad,” I said. “I’m a sprinter.”

“First of all,” Dad said. “You’re too young to know what you are, and second of all, the four hundred is a sprint.”

“It is?” I asked.

“Oh yeah,” Dad said. “There’s no pacing yourself around the field. The four hundred is an out-and-out sprint.”

I really hated this idea: run longer at the same speed. But Dad was sure that was the distance for me. And even though the whole next week I begged not to, I was running that stupid race.

By the day of the race I had convinced myself that if I ran the four hundred, I would die of a combination of exhaustion and embarrassment. I don’t know how I knew, but I felt like the old wise people who die in movies—I just knew it was my time. I glanced at my competition: six hesitant-looking white girls and Yolanda, a teammate. Then I looked at Dad who, from the look in his eyes, was trying to make my legs faster with the sheer power of his mind. I got up to the blocks wondering how I could not run this race and avoid an ass-whooping.

I thought, I just don’t feel like trucking those four hundred yards to the other side of the field. I looked at the finish line. It’s just so far. . . . Then it hit me. Wait a second, if I fell, no one would look down on me for not running. People fall. I could even be hurt. Then Dad would shake his head and say, “Why? Oh Lord, why? I’m so so so sorry ever let her run the four hundred!”

So I got on the blocks, and I knew I needed to make the fall good or no one would believe I was hurt. And so the gun went off. And I fell. And it was good.

But the dumb lady with the gun had some investment in me making it to the other side of the field, ’cause she screamed at me, “Get up! Get up!”

I ignored her, and decided to look at the dirt. Like, This is an interesting pebble. Has this always been here?

But she kept screaming, “Get up!” So I grudgingly picked myself up, and as long as I was running I wanted to do it fast, so I could get the stupid race done with and get into a bag of Fritos. And all the while I’m running I thought, What does this bitch care whether I run or not? I’ve never seen her in my life. She needs to mind her own business is what she needs to do. And I’m embarrassed, and in such a hurry to get off the field, that I accidentally come in second, meaning I lost to Yolanda. And I had to admit, four hundred yards wasn’t as long as it looked and it actually was a sprint.

I imagined Fritos were out now, though. I’ll be lucky if he ever feeds me again, I thought as I made my way over to the stands where I was sure Dad was waiting, pissed. But when I got over to him, he was with a group of parents. Rather than being mad, his eyes were full of tears and he was beaming with pride. He grabbed me by the shoulder and held his arm up pointing to me while exclaiming to all the other parents, “My girl!” And that was just the beginning.

That night he sat with his buddies, and during a lull in their arguing Dad began to recap the day.

“Mmm . . . It was at the Jesse Owens invitational. Mishna was running the four-hundred-yard dash. And that gun went off, and I don’t know what happened, but . . .” He got really singsongy, like a preacher as he continued, “I think there was something wrong with her shoes, ’cause she tripped and fell and she had lost a lot of distance. And I knew she was gonna be disappointed ’cause she had been looking forward to the four hundred for a long time, and she wanted a piece of that race. You know that’s life, right? You try to get yourself going and . . . you know the politics and such. But Mishna is on the ground, and she sees these girls getting ahead of her, and I saw a look in her eye, like a tiger who sees a fish. . . . This girl picks herself up, and she’s chasing these girls like a pit bull. She comes around that first turn and she’s already caught most of them. The girl comes in second. . . . Second, from being out of it—down—finished . . . second.”

He took a pause to gauge the attention level of his listeners before adding, “I raised ’em tough but fair. They don’t have to be number one but they have to try. You got to or, you know, the Man takes you down without a fight.”

The first recounting of the four-hundred-yard-dash story was to the fellas. The second was to anyone who made eye contact—neighbors, grocers, total strangers. And even though I felt kind of bad for not setting the record straight, I was now officially well rounded. In fact, I was almost a hero. And though I had given up on it, Dad’s approval felt good. So good that I forgot about the Sweet Beats or that I had taken a dive in the first place.

A week later we went over for dinner at Maybelline’s house. Candy had cooked and Reggie Dee was there. Anora and Maybelline sat side by side, practically eating off each other’s plates. Dad helped himself to seconds of everything and was so into the food that he didn’t notice when Candy and Reggie kissed in the kitchen. And after dinner as Dad told everyone the four hundred-yard-dash story, Maybelline’s half brother Carlos seemed truly impressed. But what I noticed was that Candy was practically in Reggie’s lap, which was weird because I thought Reggie was always over at Candy’s because Anora was in the Sweet Beats. I looked questioningly at Carlos, who was sitting on my left. He looked annoyed as he whispered, “Reggie lives here now.”

After dinner we ate ice cream while the grown-ups had another beer. Maybelline asked, “Uncle Reggie . .

. when are you gonna get us some shows?”

But Reggie was staring at Candy, his hand on her shoulders, and just said, “What?”

“Some shows . . . The Sweet Beats,” Maybelline repeated, annoyed. “What did you call them?”

“Gigs . . . yeah,” Reggie said, without taking his attention off Candy. “I’m gonna get on that.”

Anora clapped her hands excitedly. But Maybelline, who knew better, just pushed her ice cream around. She knew there wouldn’t be any gigs or any more managing.

I took a couple more bites of my ice cream and looked at Maybelline and Anora sitting across from me. I nudged Carlos and said, “You guys can do a show for me.” Maybe I was just earning my allowance.

“Really?” Maybelline asked.

“Yeah,” I said. “Carlos will watch, too.” Carlos gave me a nasty look for volunteering him. Maybe I just wanted to protect Anora from the news that hadn’t reached her yet.

“Yay!” Maybelline said, throwing her arms around her older brother. He rolled his eyes, but I knew he wouldn’t say no.

“I haven’t seen you guys in a while,” I said, looking at Anora. “I bet you’re really good now.”

“We are!” Anora said, getting up to set things up in the family room. “We really are!”

“Where do you want me to sit?” Carlos said. “And how long is this gonna take?”

“Oh stop being so weak, Carlos,” I said as Anora finished setting up a couple of chairs and told Carlos where to sit. The truth was, I liked it when Anora was happy.

So that night, Carlos and I watched as the Sweet Beats performed their first and final show. They did all their big numbers: “Push It,” “I’m Not Giving You My Digits,” and “Somebody’s Triflin’ ” with the skill and grace of six-year-olds who have had too much root beer. And when they finished they smiled and bowed, and Carlos and I clapped really loud. And then we beat the shit out of them with the couch pillows.

I'm Down

I'm Down