- Home

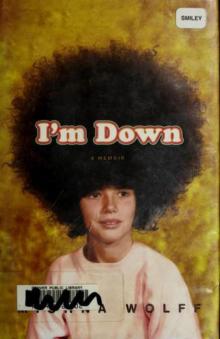

- Mishna Wolff

I'm Down Page 18

I'm Down Read online

Page 18

“I don’t know.” Mom rolled her eyes. “Your father had shit grades and even he got a football scholarship to a good school.”

That day at school I had my usual tension headache. And I wound up in the nurse’s office, as was my norm, trying to take a nap on her corner mattress that felt like it was made out of dog hair and chalkboard erasers. But even if I didn’t sleep there, the lying down acted as a reset button for me in a way that really refreshed me. And I thought Mrs. Wilkins and I were getting into kind of a groove—like she really enjoyed my visits.

As I lay there looking up at the popcorn ceiling, I felt weirdly optimistic. I had never heard of these extracurricular activities before, and as I tried to block out the crushing pain behind my forehead, I made a list on my hand of all the extracurricular activities that might help with getting me a scholarship, shooting down bad ideas as I went:

Soccer—twelve = too late to start

Skiing—too expensive to be great at

Lacrosse—too late, also hate everyone who does it

Basketball—clearly, a no

Debate—awesome, find out what it is

Cheerleading—not pretty enough, in cheerleader way—also no splits

Orchestra—check

Insect club—where do I sign?

Football—

I lingered on that one for a long time. Football had worked for Dad. And the idea of running into things really fast seemed like something that would be good for insomnia.

I was drifting when Mrs. Wilkins woke me from my half sleep to send me back to class. As I stretched she said, “I don’t want to see you in here tomorrow.” And I nodded, a little hurt and embarrassed. I thought we had a connection, but I guessed she was just being a nurse.

That night when I got home to Dad’s house, he was wrestling with Yvonne. Andre and Yvette were trying to help their mom win, and were hanging off Dad’s arms in a way that begged the question: Why doesn’t he just fling them? Yvonne had something in her hands that I couldn’t see, and as Dad tried to pry it from her, she laughed and squealed, “Don’t, John, no!”

I set my book bag and violin down and watched, of course, wanting to see what was in her hand. But Dad immediately involved me saying, “Mishna, grab her arm!” And instead of choosing sides I stood next to Yvonne, looking like I wasn’t quite sure what an arm was or how to grab one. Dad was annoyed with my lack of assistance as he proudly lifted a pack of cigarettes above his head shouting, “Busted!”

“It was just this one time.” Yvonne tried to grab them again, but failed.

“Kids,” Dad asked, “does Mommy smoke?”

Yvonne put her finger to her lips.

“Yes,” Andreus said.

“Andre!” Yvonne cried.

“Busted!” Dad repeated. “You are so busted.”

“Dad,” I said. He, Yvonne, and the kids turned and looked at me like I was from the moon. It was then I realized I had interrupted.

“I’m sorry. I interrupted.” I grabbed my bag and started heading downstairs.

“What is it?” Dad asked impatiently. “You don’t gotta huff off.”

“Well,” I said, unsure now. “Today I decided that I want to play football.”

Dad didn’t look as stoked as I thought he would, and he and Yvonne said in unison some version of: “You’re a girl.” And Yvette the three-year-old just started giggling.

“I know that,” I said. “But there are, like, girls’ leagues, right?”

“Not that I know of!” Dad said. “And even if there were, you’re skinny. You’ll get hurt.”

“She’s not that skinny, John,” Yvonne said.

“I’m not!” I repeated. “Plus, I’ve never broken a bone, ’cause I’m strong!” I tried to make myself look more muscular. “And you got a football scholarship to college, right? Maybe if I get good I can get one, too.”

“Well . . . ,” Dad said, not wanting to burst my gender bubble yet. “Football doesn’t start until the fall, and if you can gain twenty pounds between now and then you can play.”

“Awesome,” I said.

“But if you’re suddenly feeling athletic, no need to wait till then to get competitive. Let’s get you into a summer sport now.”

“I don’t want to do track again.”

“I want to play football!” Andre shouted, causing Dad to smile uncontrollably. Dad picked him up and kissed him on the forehead, holding him as he continued to talk to me.

“What about summer swim league at Medgar Evers?”

“Cool!” I said. “Wait . . . It’s like laps, right?” Suddenly I realized we wouldn’t be playing Marco Polo.

“You race. It’s a team,” Dad said.

“Okay,” I replied—sold but not quite sure how I had gotten thrown off football.

“A’ight, then,” he said. “You swim this summer.”

“And in the fall I can play football?”

“Twenty pounds.”

“Wait, wait, wait!” Yvonne said. “You’re rewarding your daughter for bulking up?”

Then Dad whispered something in Yvonne’s ear, and she laughed a little. I imagined him saying, “Don’t worry. She’ll never get enough to eat in this house.” But it was probably just something about Yvonne’s butt, and how big and awesome it was.

I swam on the league at Medgar Evers Pool where we trained and then did little meets against other rec center pools. And I couldn’t tell how good I was, but the rest of my team was really horrible—which after being on the Satin Dolls was super refreshing. There were people on the team who were afraid to jump into the deep end, and every race involved a lot of slapping and splashing. So I couldn’t really rest on my laurels knowing I was better than people who looked like they were drowning. Still, I found that there was one stroke I was undeniably good at—breaststroke. And I got blue ribbons for it, lots of them. I also got teased to no end, thanks in part to the fact that the coach referred to people who were good at breaststroke as “her breasters.”

Still, as much as I had fun swimming, I just saw it as a way-station till I could bulk up enough to start playing football. And I focused tirelessly on gaining weight. After swim practice ended I would go down the street to Thriftway, a very low-priced neighborhood supermarket that sold a generic brand called Western Family. I knew Dad would be late to pick me up, which gave me enough time to buy my bulking agents. I had read the labels, so I knew that the highest calorie content for the cheapest food that didn’t make you throw up was Western Family fruit pies—five for a dollar. I tried all of the flavors, and my favorite for bulking was lemon because I thought the sourness of the lemon made it even easier to keep down. Vanilla and chocolate were fun but they actually would make me hurl—and cherry was for dessert. I would consume my pies as quickly as possible on my way back to the pool and hide any evidence of eating them, because I still wanted my pork chop at dinner. But every day when I got on the scale at the pool my weight seemed to be the same. By the halfway point of swimming season, I still hovered around eighty-seven pounds. I began to give up hope of ever getting a football scholarship. And I also spent a good deal of time mentally redecorating my future shack and finding clever ways to work with the water stains.

One night, I was over at Mom’s and I got one of my tension headaches so bad that she had to give me four aspirin.

“I’m gonna talk to your dad about your stress level,” Mom said. “I think you have anxiety and I think that maybe you should be spending more time at my house now.”

“Yes,” I said, hardly containing my delight. “Maybe you’re right. I’m soooo stressed out.”

“Well, I’m gonna talk to him.”

I was amazed. Mom had always been a little intimidated by my dad and had always agreed with his custody arrangements. But if she was now willing to talk to him about changing things up, I couldn’t be happier. She kept the fridge full and her house was clean and quiet—all things I liked.

The next day when Mom went to drop me and

Anora off at Dad’s, she said she wanted to talk to him. “Okay,” Dad said. “What’s on your mind, Diane?”

“Well,” she started, all of a sudden getting squirmy, “I feel like Mishna would maybe do better spending a little more time at my house.”

“Are you saying you’re a better parent than me?”

“No . . . Here’s the thing,” Mom said, sounding confused. “Mishna has these headaches—”

“What headaches?” Dad asked. “She doesn’t have headaches at my house.”

“She has them at school a lot.”

“You’re feeding them stuff.”

She paused. “The nurse and I agree. . . .”

“What nurse?”

“The school nurse.”

Dad looked at her and said, “It’s summer. Mishna’s not in school.” Mom stammered, she was losing her train of thought in front of my eyes. It’s like Dad was made out of kryptonite.

“Listen,” Dad said, grabbing Mom’s lower back and leading her toward her car, “this is the first time I’m hearing about any of this.”

“Really?” she said.

“Yes,” Dad said. “Mishna hasn’t mentioned any headaches to me.”

“Oh,” Mom said as Dad opened her car door.

“So, I’ll talk to Mishna and together we’ll get to the bottom of it all.”

“Okay,” Mom said. “That sounds reasonable.” Dad shut her door and walked back up to where I was on the back steps. He passed me on his way into the house and said, “Your mom’s a control freak.” And that was the end of that.

The summer swim league was almost over when, after practice one day, a blond guy named Dan who seemed to work at the pool approached me. His hair was white from chlorine, and had the consistency of cotton candy. And he was shaped like an upside-down triangle. He even walked on the outside edges of his feet, which folded in to make the triangle’s bottom point.

“I noticed your breast,” he said without a tinge of humor. “If you wanted to keep swimming into the fall, I’d like to try you out on CAST, our swim club.”

“Hmmm,” I said. “I was planning on trying to get a football scholarship, but I’m not big enough yet.”

He snickered in a way I found arrogant. “You might want to consider swimming then . . . on a real USA Swimming club.”

“Does it cost money?”

“Yes.”

“Oh,” I said, dismayed.

I turned to leave as the conversation was over, when he said, “We really need a breaststroker, especially for the relay. The board has talked about scholarship spots. Maybe we can work something out.” Then he said the magic words, “Do you want me to talk to your parents?”

“Absolutely!”

So in the fall I started training with the Central Area Swim Club or CAST. In addition to finally being good at a sport, the great thing about swimming was that Dad knew almost nothing about it. Still, when he would show up at meets; lack of knowledge didn’t stop him from trying to coach me at competitive swimming.

Before I got on the blocks for my events he’d pull me aside from my teammates and say, “Can we just take a second to talk about your race?”

“Yes, Dad,” I’d say, waving my teammates along. Then trying to mask my sarcasm, I’d ask, “How do you think we should handle this one?”

“Well,” he’d say, scratching his chin. “I think you should take the first lap just real fast.”

“Great idea!”

“Then when you get to the second lap—go for it! Don’t try to coast off that first lap. . . .”

“Okay, Dad.”

“The third lap you just want to give it all ya got.” Then he got really serious, “Then on that fourth lap, you just bring it on home—fast as you can.”

Then I would go talk to my coach, Dan, who would tell me what my competition looked like and what it would take to get me into the finals. Always telling me to “streamline” and to “explode off the walls.” Then he’d remind me, “A winner is someone who finds the absolute limits of personal agony, and surpasses them every day.” Then whatever was gonna happen would happen, and I would get a hot dog.

As months went by I got a little bigger, and even though swimming was fun, I was sure that football was more important to college types, and I was eager to solidify my future.

“Dad,” I said one afternoon after swim practice, “I think I’m bigger now, and when I checked the scale I gained a few pounds. Hey!” I flexed. “Look at these arms.”

“That’s great, baby,” he said.

“So?” I said expectantly. But he just looked at the road. “Dad!”

“Don’t yell at me.”

“Sorry, Dad. But you said I could play football—”

“When?” Dad asked.

“That I could play football, if I got bigger!” I couldn’t believe he was drawing a blank. “That’s why I was swimming this summer . . . ’member?”

“Those boys would crush you, baby,” he said.

“Well, I can play with the girls. I’m bigger now!”

“Damn, Mishna,” he said impatiently. “When are you gonna get it through your head? There is no girls’ football!”

“There is,” I said. “There must be.”

“Well, there’s not!” he said. “Besides, I would never let you play football. What’s wrong with you?”

“But you said . . .”

“I never said you could play football . . . that’s crazy.”

“It’s not crazy,” I said, not really sure why I was starting to cry. “I want to get a football scholarship!”

“Well, no one is giving them to girls!” he said. “What you ought to do is get yourself a swimming scholarship or something. ’Cause football ain’t on for you.”

“But,” I said, still crying, “nobody likes a swimmer. It’s not like you sit down and watch Monday night swimming.”

Dad looked up from the road and said, “We don’t have that kind of cable.”

That night dribbled by slowly. My life plans all shaken up, my fears of the future multiplied as I helped Dad with dinner. And my good ol’ tension headache came back in the middle of Yvonne’s grace.

But as I picked at my chicken thigh—my purpose for eating evaporated—part of me still wondered if what Dad said about women’s football was true. I mean, maybe there were teams and he just didn’t know about. Secret women’s football teams that met at night and played by candlelight. He didn’t know everything and I decided that before I made myself crazy, I should get a second opinion.

So after dinner when I saw Zwena out on the street with Nay-Nay, I ran out of the house. Zwena had started hanging out with Nay-Nay in the last year or so, and after school she would change out of her uniform into something closer to what Nay-Nay wore, which at the moment were big gold earrings and bright-colored jeans. I was always still happy to see Zwena, but I thought she looked ridiculous in her red jeans. And she was wearing cheap hoops so big, it looked like her ears had been handcuffed and were trying to break free before the fake gold turned them green.

Both the girls were about sixteen now, but looked about twenty-two as they leaned against Nay-Nay’s father’s Caddie and flirted with a light-skinned boy with a fade. Nay-Nay had a bag of cheese puffs and in between bites she would lick the orange powder off her fingers like cheese powder was a delicacy.

“Yo, Zwena,” I said, walking up to them and getting my guard up a little for Nay-Nay.

“Hey, violin!” Nay-Nay said, not bothering to take her fingers out of her mouth. “Where is your violin?”

“I dunno,” I said. “You must have eaten it.” That landed a little harder than I had intended, because Nay-Nay raised her hand to hit me. But when I flinched everyone laughed—and her dominance was reasserted.

“S’up, Mishmash,” Zwena said, acting a little more street for Nay-Nay. Then she pointed to the boy beside her. “This here is Ty.”

“Hey,” I said. “I’m Mishna.”

“Don�

�t you go wit’ Bijon?” he asked, referring to a light-skinned boy who lived nearby.

“No!” I said incredulously. “He’s gross.”

“Would you like to?” Ty asked.

“Shut up, Ty!” Zwena said.

“No!” I said. “I barely know Bijon!”

“Okay. Dang,” Ty said. “You ain’t gotta yell.”

“Whatever,” I said, dismissing Ty, and then asking the girls, “Hey, do you know any girls’ football teams?”

“Nope,” Nay-Nay said.

“Maybe . . . ,” Zwena said.

“You’re tripping,” snapped Ty. “There’s no girls’ football teams, not at Miller or RB or CAYA.”

My heart sank.

Zwena said, “I know a girl that played football with the boys, though.” She turned to Ty and Nay-Nay. “’Member Shanda?”

“Oh yeah . . . Shanda,” Ty said, giving me a glimmer of hope, before adding, “She was a ho.”

“She was not a ho!” Nay-Nay said—half-eaten cheese puffs falling out of her mouth. “Why you saying that?”

“Because it’s true,” Ty said. “She slept with that whole damn team.”

“That’s what I hear,” Zwena said. “She was on that team ’cause she was hoin’.” I didn’t like Zwena saying hoin’. She was a mathlete.

I continued, “Maybe she just really liked to ram things with her head and tackle and stuff.”

“Now that don’t make no kind of sense,” Zwena said. “You’re crazy.”

“So there are no girls’ football teams?”

“What, are you deaf and dumb?” Ty quipped.

“You want to play football, violin?” Nay-Nay laughed. “You better stick with playing your violin and making out with Bijon.”

“I met him like once!” I yelled, and stomped back into the house all bummed out thinking about was how I was never going to college. And on top of it I didn’t think Zwena liked me anymore.

The next week at swim practice I was too depressed to train. I loafed my way through every workout and stopped eating fruit pies. I was good at swimming, but I didn’t really get the point of it anymore. You just swam really fast for the sake of swimming, big deal. It wasn’t like football where people give you college money for it, and scream at the TV, and throw parades where mooning and head-butting might occur. By Friday practice, Dan took me out of the pool. He sat me down by a chalkboard where our team mantra was written.

I'm Down

I'm Down