- Home

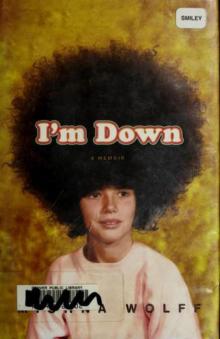

- Mishna Wolff

I'm Down Page 17

I'm Down Read online

Page 17

On the morning of our first game Dad woke me up smiling with my jersey in his hands. He had such hope in his eyes—it was like he was holding a fresh lotto ticket. I almost felt guilty as I limped out of bed dramatically and said, “Dad . . . Wow. My ankle really hurts. I don’t know about playing.” Then I made a show of walking and wincing. “Yeah, I think this ankle’s gonna be a problem.”

“That’s okay, I gotcha covered!” He magically produced a roll of athletic tape.

“What’s that?” I asked.

“We are gonna tape your ankles up,” Dad said. “It’ll give you the support you need.”

Fuck! “Um, won’t my game play suffer?”

“Nah,” he said, propping my leg up and taking tape off the roll. “I used to do this all the time.” He smiled as he wrapped my foot. “Guess you got my ankles!”

I thought I was gonna be sick.

Remarkably, once I took the court and started playing, my fears were quickly assuaged. There was nothing I could do to make this team lose. The Satin Dolls were a well-oiled machine. We set up plays, we stole, we rebounded, we blocked, and we hustled. And the opposing team ran around the court like twelve-year-old white kids that had played three months a year for the last two years, while their disturbed parents ran around trying to verify that we were, in fact, all twelve.

When the game ended, the Satin Dolls all breathed a sigh of relief and there were high-fives all around. We had beat the team we were playing 54–12. It was reassuring to have such a colossal win our first game out. And Coach Wheeler even smiled, deciding to put off telling us about all the mistakes we made until Tuesday practice.

The next week we played a North End team called Queen Anne, whom we beat 62–7. And the following week we beat a team called Laurelhurst 79–2. They naturally scored those two at the free-throw line. A seventy-point lead wasn’t gonna keep the Satin Dolls from flagrant fouls.

I, however, played that game like a lady. I shared the ball with my teammates and I tried not to touch anyone I wasn’t supposed to. And if I somehow wound up invading someone’s space even in a perfectly reasonable basketball way I promptly said, “I’m sorry.” This, juxtaposed against my teammate’s frothing aggressiveness, really pissed Dad off.

Dad taping my ankle for games meant him later removing the tape, which gave him plenty of time to tell me how disappointed he was in the way I played.

“You know,” he said after the Laurelhurst game. “It’s like you’re playing, but you’re not playing. . . . Let me just rip the tape off quickly.”

“No, please,” I said. “Let’s just leave the tape on. I can learn to live with it.” I imagined the tape turning into a smelly goo, which could be the next penicillin and win me my scholarship.

“I’m just thinking,” Dad continued, slowly ripping tape off my foot. “That you’re playing like you’re scared . . . you can’t be scared of nobody.”

Then he whipped out his trusty jackknife. “You want me to cut it off?”

“No!” I screamed. “But you can rip it off quickly.”

“You know, you could be a lot tougher on D.”

“But, Dad,” I said. “The other team didn’t even score.”

“Still, you’re letting your teammates do all the work. You need to get in there. I saw about three layups you could have grabbed instead of Shawanda.” At this point I wondered if he even knew who the fuck he was talking to. By not playing, I was being a team player, and clearly, it worked. I was sacrificing personal glory for the benefit of the greatest numbers. Duh. And I wasn’t willing to mess these girls up so that he could be proud.

But Tuesday after practice Coach Wheeler stopped me on the way out of the gym. “Wolff!” she said. “I’m not sure if you’re an asset or a liability.” I nodded as though I hadn’t heard it a hundred times. “This here is basketball. If you’re out there, you play.” I guessed she didn’t like winning.

“I’ve been trying to just get the ball to Keisha.”

“As long as you guys aren’t in trouble, you can take a shot or two.”

“I’ll gauge it,” I said. But what I was thinking was, Why is everyone so hung up on me play-playing? The status quo is making everyone look good. Coach Wheeler gets her wins, and Dad gets his winner, who cares whether or not I learn to play? Not me.

The Satin Dolls cared, though. And almost as if instructed, during the next few practices they passed to me, and they didn’t grab my rebounds. But it was practice, and that’s what practices were for—practicing.

The next weekend we played Green Lake, and all through the first half, when I passed the ball to Shawanda or Leslee, if I had the shot, they passed it right back to me. And as well as having Coach Wheeler shouting at me, I now had Dad telling me to “Take the shot!” or “Grab that!” which made me positively skitzy.

At halftime when the coach let us drink, I caught up with Shawanda and Leslee at the drinking fountain.

“What the hell’s going on?” I asked.

“Coach said that we could lean on you a little more,” Shawanda said.

“There’s only seven of us, you know,” Leslee said. “That’s a lot of running.”

I had never thought of it that way and asked, “Aren’t you scared I’m gonna mess up?”

“Nah,” Leslee twanged. “You gotta learn someways, right?”

I couldn’t wrap my head around how generous they were being. It was the opposite of what I was used to at school. When I had been the weak link on the math team, Kirsten got me booted because she felt I was holding everyone back. And Violet kicked me out of our quartet when Claudia, a better violinist, became available. These girls needed the city championship like I needed oxygen and yet they were still trying to include me.

“Well,” I said to Shawanda, still nervous about it, “Keisha seemed to get pretty mad when I missed that shot from inside the paint.”

“We can afford it,” said Shawanda. “Just try not to mess up. And grab more rebounds. You’re tall.”

“Okay,” I said, and I headed back to the bench for the second half.

The second half I took three shots and missed three shots, but grabbed a few rebounds and made two shots at the free-throw line. And the whole time Dad and Coach Wheeler alternated screaming at me and covering their eyes. But it’s not like I could have possibly held us back. We won the game 79–0, with Keisha scoring fifty-two points and Shawanda scoring sixteen. I scored my two and hustled on defense and didn’t incur one foul in the process. And when we left the opposing rec center I thought clear as a bell, This shit is kinda fun.

The next week my whole family came to the game. Yvonne, Anora, Andreus, Yvette, and, of course, Dad. And walking onto the home court that morning, I was glad to have my family there. Not because I wanted them to see me—but because my team was pretty amazing. The kind of thing one really has to see to believe.

Upon arriving, Yvonne instantly became impatient and fancy.

“Ooh, John,” she said, turning up her nose as they walked in. “You smell that? It smells funky in here. Like too much activator . . . something nasty.”

“It’s a gym,” Dad said. “What do you expect it to smell like?”

“My gym growing up didn’t smell like this,” she said, putting on her airs. “And look at her teammates. G-H-E-T-T-O. They look like they just got out of juvie.”

“Well,” Dad said. “They can play like a mofo.”

“Well,” she said. “Maybe we should go at halftime. I don’t feel comfortable here. You know there was a stabbing here in September.”

“I’m gonna watch my daughter play a little basketball,” Dad said. “If you need to go, just come back with the car in like an hour or so.”

Yvonne was angry and said, “I guess I can watch for a little bit.” She turned to me, “So bring your A game, Duck-Butt!”

When it was time for me to leave my family in the bleachers and take my place with the rest of the team on the bench, Keisha looked up at my stepmother and st

epbrother and -sister in the bleachers and said, “That’s your family?”

“Yeah,” I said, a little cautious. People didn’t always know what to make of our different colors and how they worked. Andre and Yvette were a lot lighter than their mother, so they looked like they might be Dad’s, and my sister had curly dark hair so she looked like she might be mixed with something. And I was white as the day is long. As I watched Keisha’s and Shawanda’s faces as they tried to figure out who was related to whom and how many marriages were involved, I could feel my preppy alabaster sheen warming into something they could relate to.

“Is that your half sister?” Keisha wanted to know.

“No,” I said. “That’s my full sister!”

“Really?” Leslee said. “You guys both white?”

“Now it makes sense,” Shawanda said.

“What?”

“Just your whole thing,” she said.

That was when I noticed someone on Montlake, the opposing team, was waving to me. In the middle of their line up of affluent white faces was Eileen Connoly, smiling and waving her arms so I would spot her. I tried to pretend I didn’t know her, but I could feel my cred with Keisha and Shawanda diminish incrementally the more she tried to get my attention. Finally, I relented and waved a little wave back.

And as we took the court and I stood across from her in the tip-off she said, “Wow. This is your team?”

“Yeah, this is my team.” I was talking to her, but I didn’t feel like I was the same Mishna that she knew. I felt like a Satin Doll. “No hard feelings, okay?” I said.

“What?” she said.

“When this is over.”

“Yeah, whatever,” she said. But I knew she probably wouldn’t want to talk to me after what we were about to do to her and her teammates. The Dolls were no longer happy with winning. It wasn’t a win to them unless the other team didn’t score. Any bit of allegiance in this environment was to those six girls who were better at basketball than Eileen was at algorithms.

As the game began there was a marked difference in my game play. I played more aggressively than I ever had before. I looked at Eileen and her soft, spoiled teammates who all looked like her—like my friends at Oksana’s house—like everyone I went to school with. And I resented the fact she was even playing basketball. And the resentment felt so good that I stole the ball from her midcourt and immediately threw it to Keisha. But the next time the ball came to me, I took a chance on a three-pointer and missed.

At halftime Coach Wheeler said to me, “You’re getting cocky, Wolff.” But I didn’t care. If cocky was the drug I was high on, let it flow. I felt like I was having a good time out there. Either that, or I was mad at everyone, and running and jumping was making it better. And in the second half I thought about Eileen’s snobbery about how I had NEVER been to Europe!? And even though I didn’t really have to, I elbowed a pudgy girl with my left hand while dribbling with my right. And I did it for the weirdest reason. I did it because I didn’t like a white person thinking they could guard me. That was when the referee blew his whistle and I received my—very—first—flagrant—foul. And it was so flagrant.

I wasn’t worried about the foul hurting the Dolls. This girl had a better chance of curing cancer than making her free throws. Besides, I had Shawanda and Leslee to grab the rebounds.

Now I know why these girls play basketball, I thought. I felt so strong.

When the game was over we had won 67–2. But on Tuesday we’d all be kicking ourselves for letting that one basket get away.

We had to go down a line and tell the Montlake team “Good game.” And as I moved through the line I made sure that I was the last one to get to Eileen. Eileen looked at me, waiting for me to apologize to her or soften the blow of that steal, and what we had done to her team. Every instinct in me knew to conduct myself with humility and try to make her feel better. But I just couldn’t and after slapping her hand I said, “I told you . . . no hard feelings.”

“Well, it’s just for fun anyways,” Eileen said.

“For you guys maybe,” I said, and we were both quiet for a second. “Well . . . I guess I’ll see you Monday.”

“Yeah,” Eileen said, and walked away. And though I knew I’d pay for my cockiness on Monday, all I could think was, I really got a flagrant foul!

Eleven

EXTRACURRICULAR

I LOOKED AT the clock. It was 4 A.M. I had been up almost all night and soon my alarm for school would go off. I had been worrying again, and at this point lack of sleep was a more pressing fear than my previous ones, which I think was the point of staying up all night worrying. It was the third night in a row, and the next day was going to be brutal. The result of these late nights was midday tension headaches that started behind my forehead, and sent me to the nurse Mrs. Wilkins’s office. I had written myself a note and had Mom sign it authorizing Mrs. Wilkins to give me Tylenol, but my ass-kicking headaches laughed at Mrs. Wilkins’s girly little Tylenol.

Jesus! I thought. I’m going to be a wreck tomorrow! Even if I fall asleep right now, I’ll still only get 150 minutes of sleep. I tried a number of positions and then looked at the clock again. One hundred and forty seven minutes of sleep. The red digital numbers on my alarm clock were taunting me and I finally put a pillow over the clock to stop it from making fun of me. Not only did I have insomnia, but I was aware that I wasn’t supposed to have it at my age, causing more worry: maybe I was causing permanent brain damage, maybe I needed it.

I hurled myself out of bed and stumbled into the kitchen of Mom’s apartment. I poured myself a glass of milk and was mixing in some chocolate syrup when Mom stepped out of her bedroom in her bus-driving uniform. She grabbed her work bag and saw me standing there, wide awake in my nightgown. Her face radiated concern.

“You can’t sleep again?” she asked.

I nodded as I stirred my milk.

“Are you like this at your dad’s house?”

“Sort of,” I said.

“Well,” she asked. “What the hell is keeping you up at night? What are you worried about?”

“I think about how I’m not sleeping.”

“Well, why aren’t you sleeping? Are you scared of something?”

I thought about it for a second to see if it was gonna hurt her feelings before I said sullenly, “My future.”

I think she thought I was gonna say “Bears,” because she looked annoyed. “You’re twelve!”

“I know . . . But I’d like to have some financial security when I’m older. The rest of my friends are gonna go to great schools and be doctors and lawyers and stuff.”

“So will you,” Mom said.

“How?” I asked.

This was not a question Mom was ready to face at four in the morning and she tried to sound blasé as she said, “You’re poor and smart. You’ll get a scholarship or something.”

Her lack of concern only worried me more. “But what if I don’t?”

My mom was silent. It was not reassuring. Finally she said, “Why do you care about all this stuff?”

“Because now is when you start planning!”

“We’ll plan it when you get closer to going.”

“Okay, but I really want to go to Stanford, MIT, or Penn.”

“The University of Washington is a very good school.”

“Not to my friends,” I said, tearing up. “They laugh at it. And I don’t want to be poor my whole life. Poor people go to the University of Washington.”

“You sound like a Republican.”

“Well,” I cried, “I just want to have a lucrative anesthesia practice like all my friends. And at this rate, I can’t see that happening!”

“Your dad and I didn’t finish college at all.”

I sobbed. Loudly.

“Listen,” she said in her “don’t cry” voice. “When you see the future, what do you see? I mean, what do you envision is going to be so bad?”

“Well,” I said, “there’s this shack�

�”

“Whoa!” Mom said.

“Can I finish?” I asked. She nodded. “There’s this shack and there’s a mattress on the floor . . . no sheets.”

“Uh-huh.”

“And the mattress is stained like all different weird-colored stains. Like you can’t tell what the stains are from—”

“Okay,” Mom said. “I gotta stop you here.”

“Wait,” I said, and spit out really fast, “And I die of hepatitis from bad water. The end.”

“Wow,” Mom said. “How do you come up with this stuff?”

“How is that not gonna happen?”

“Listen, I have to go to work now. But I think you might have a little bit of black-and-white thinking about how people become rich and poor. Will you call me from your dad’s?”

I wasn’t sure I wanted to take advice from her. She still had student loans, no degree, and two kids. It wasn’t the type of security I was looking for.

“I promise,” she said as she headed out the door, “that there are a few steps between Stanford and a shack.” But it didn’t seem that way to me. My friend Marni lived in a glass palace on the ocean, her dad had gone to Wharton—Dad’s friend Randy, who lived in an alley, had gone to the University of Washington. And no one had sat me down for the “crack talk” yet.

“Besides,” Mom said, “there are a lot of ways for people to get scholarships. Just do extracurricular activities.”

“What’s that? Extra . . .”

“Extracurricular activities. Like your violin is an extracurricular activity,” she said.

“Really?”

“You do orchestra. Do it in high school.”

“I was already planning on it.”

“And there are clubs, and student government . . . and sports is huge to colleges.”

“Sports? You saw me at basketball. I’m not athletic.”

“You are. You get it from your dad.”

“I’m not,” I said. “And I don’t think that would be a factor at the schools I’m thinking of. I think it’s just grades and stuff.”

I'm Down

I'm Down