- Home

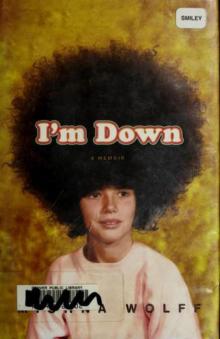

- Mishna Wolff

I'm Down Page 2

I'm Down Read online

Page 2

Latifa and I spent an afternoon on the swing. I even tried throwing dang around a couple times, saying, “Dang, I like swinging—dang.” Or “Dang, I’m swinging fast—dang.” And when it started to get dark, I climbed into the house exhausted from fun.

But the next day, Latifa came back with Jason, Nay-Nay, Dorina, and three new kids. They immediately made it clear “my turn” was never again, and they found every way possible to turn a swing into a weapon. First they invented “swing bombing” where one person hurls the swing at a friend, causing them to bruise or fall over. And then they changed the game to twisting the rope up as tight as possible, and everybody piling on the swing and releasing it to let it spin. They spun at a nauseating speed while simultaneously trying to throw each other off onto the sidewalk. Then they would laugh and wipe their wounds and get back on to go another round. Nay-Nay pushed Jason so hard that with the added centrifugal force of the swing, he cleared the parking strip and landed in the street. “Dang!” he said. “I just got my hair cut!” Then he grabbed her by her shirt and tackled her to the ground. I stared as Jason and Nay-Nay took turns smushing each other’s head into the parking strip. That is, until Jason looked up at me and said plainly, “What are you looking at, whitey?” And I answered his question by running into the house.

That was when Anora, my three-year-old sister, tottered out the front door, consumed with excitement, and began crawling down the front steps feetfirst as fast as she could. She was wearing a striped T-shirt and her curly dark hair was pulled in a ponytail over her head like Pebbles from The Flinstones. And, having cleared the stairs, she instinctively moved to the center of the action like a tank. Her blue eyes were ecstatic. I watched her from the dining room window, afraid that she would get hurt or banished or made fun of. But she just stood next to Dorina clapping her hands together, laughing, “Again! Go again!” In fact, she was being so adorable that Latifa walked over to her from the opposite side of the swing to try to help her up onto the swing. But Anora just screamed and hit Latifa’s arm. And rather than getting angry, Latifa begged Anora to let her pick her up. And watching the scene in front of me I couldn’t figure out how Anora was a sister and I wasn’t, but she was my sister. And then Mom got home.

Her expression was already frustrated as she pulled her car up to a gang of rowdy kids playing king of the mountain on my tire swing. And as she parked, her face went from frustrated to frightening. She got out of the car, glared at the kids, and silently picked up my little sister as she marched into the house. She set my sister down in the dining room before she walked up to Dad.

“John, what’s going on outside?” she asked.

“Oh . . . that’s Mishna’s tire swing,” he replied, not looking up from his paper.

“How is it Mishna’s?”

“Well, damn,” Dad said. “It’s not my fault that she’s up in here!”

“John, those kids have taken over our front yard!” Mom was usually afraid of Dad, but the fact that he was still reading emboldened her. “Is that your idea of helping Mishna?”

“Listen,” Dad said, “the girl needs to learn how to fight for her shit.”

“There are six of them,” Mom said. “And they are twice as big as her.”

Dad looked up from the paper finally—to make a point—and said, “Yeah . . . that’s how life is.” And with that, Mom walked out the door, grabbed a saw from the garage, marched through the gang of kids, and cut down the tire swing. I guess she didn’t care about popularity as much as Dad did.

This wasn’t bad news to me. It meant the next day I got to stay in the house with my daddy, which was all I had wanted to do in the first place. And while Dad and his main crew sat and played dominoes, I tried to make myself as small and fly-on-the-wallish as possible, while still pretending like I was one of them. When beers were passed around, I shook my head as though I were declining their invitation. When they picked their dominoes, I was always, “Just sitting this one out.” And when they yelled about football or politics, I scratched my chin as though they had a good point, but was still forming my opinion. There was also a lot of yelling at Dad for cheating.

Everyone knew Dad cheated whenever he could. He was a cheating machine—cheating at everything from cards to Candyland. And Eldridge, a huge caramel-colored man from Texas, was the loudest in the group—which made it his job to catch Dad cheating. That day he decided that the best way to get my dad to play an honest game was to teach me how to play dominoes. As he said, “No self-respecting father would cheat in front of his own daughter. So we just got to educate you!” So as the day went on, Eldridge showed me how he was playing, and how the points were counted. And when he wasn’t teaching me, he watched Dad like a hawk.

But I wanted to apply some of this learning.

“Dad?” I asked “What if I just played one game with you guys?”

“You just sit there and be seen,” he said, meaning, “not heard.” And I shut my mouth. That is until a few minutes later when Dad made a questionable shuffling move.

Eldridge stood up and shook his finger, shouting, “Oh no, John! No way!” Then he turned to me. “Lil’ girl Wolff, you saw that shit! You had to—you’s right there.” He got in my dad’s face again with the finger. “You were done shuffling and you picked up some dominoes, decided you didn’t like ’em and put ’em back in the pile like you was still shuffling!” He gestured to me. “Even your girl saw it! Shame on you!”

My dad retorted, “Eldridge! You trippin’!” Then threw up his hands like this was taking too long and said, “I thought we were playing some dominoes.”

Eldridge turned to me again. “Lil’ girl Wolff! Lil’ Wolff! Did you, or did you not see your father pick those dominoes up, decide he didn’t like them, and then put them back in the deck like he was still shuffling?” Then he said softly, like it was paining him, “Oh, your daddy cheats. He cheats so badly.” He shook his head and looked at my dad again, but this time like he was worried about him and said, “When you go to church you oughta beg the Lord to forgive you for cheating.”

“Are you done with your little performance, so we can play the game?” Dad said.

“No. I am not done,” Eldridge said, turning to me, “So, lil’ Wolff girl, did you see your daddy cheat?” He lowered himself so he was looking right into my eyes and said, “Jesus is watching.”

Dad glared at me across the table—he might as well have been sitting there actually opening a can of whoop-ass. It was Jesus or a can of whoop-ass, and I didn’t want to be one of the guys anymore. I wanted to take my chances with Nay-Nay.

“I didn’t see anything,” I said.

“See,” my dad said to Eldridge. “You got nothing.” Then he turned to me and said, “Mishna, why don’t you come up here, play this round.”

“Play dominoes with you guys?” I asked.

“Well, you know how,” he said, and pulled up a chair next to him, which was the coolest thing that had ever happened to me.

I got my own dominoes and was playing at the table right along with the guys and my dad. I had died and gone to heaven. And I sat with the fellas, thinking, “Yeah, this feels right. Playing a game with friends—eating peanuts . . . I wish Nay-Nay could see me now.”

Dad even gave me a few swigs of his beer—and I knew he was proud. I mean, these weren’t the sister friends he had wanted me to have, these were better, these were his friends. And as I scored my points, I let my mind wander from the game to a fantasy of my dad taking me out for ice cream. He’d muss my hair and say, “You know I didn’t think you were cool for a while . . . BOY WAS I WRONG! You are so fun and good at dominoes!”

But the tone changed when Big Lyman showed up, and the fellas started pulling out their money. My dad pushed my chair away from the table and said, “You need to sit this one out.”

“Why can’t I play?” I asked.

My dad rubbed his chin, trying to find a way to exclude me without having to have, “The Gambling Talk.” But Eldridg

e took up the parenting slack, saying to me plainly, “You can’t play, lil’ Wolff, because you don’t have any money.”

“I have my piggy bank.”

To which Reggie said, “Shoot, then, let her play.”

But Dad wasn’t having it. So instead of just sitting and watching idly, I decided to make myself useful and help my dad out by telling him what dominoes I would play if I was him. I saddled up beside him and surveyed the lay of the table before whispering in his ear, “Dad, play the one with the three and the five.” I wanted all the other guys to be jealous, that they didn’t have the same secret weapon as my dad.

But I guess I wasn’t as quiet as I thought, because Reggie Dee turned to Big Lyman and said, “I heard that! John got a five!” Then he repeated himself, “I said, John got a five . . . sho’ as a black man has dick!”

My dad’s face soured, and he pointed angrily at the door. “Mishna, downstairs.” And I slumped out down to my room.

From downstairs I could hear an argument start. There was shouting and banging. I wondered what was going on up there and if there was another version of dominoes with tackling. I sat on the floor of my room for the half hour while they were yelling, and I did some pretty bitchin’ coloring. And when I heard Reggie’s and Big Lyman’s cars pull away, I switched to playing with Speak & Spell.

When I headed up later, one of the dining room chairs was broken and lying on the floor. And as I walked through the living room into the hallway, I heard Dad’s voice.

“Mishna.” I turned the corner and found my dad perched on the edge of his waterbed.

“Am I in trouble still?”

Dad and his buddy engrossed in a game of dominoes.

“No. I want to show you something,” he said, and reached into the drawer underneath the bed.

“What?” I asked as Dad produced a shiny revolver.

He held it in his hand about one foot away from me. “Do you know what this is?”

“A gun?” I asked.

“Yes, it is a gun,” he said, holding it up. “It’s a three-fifty-seven Magnum.”

“Oh,” I said, a little intimidated.

“This is here for protection,” my dad said. “It’s always in the house and it’s always loaded, you got that?” He put it in my hands and I had to fight the urge to drop it.

“Yes . . . But why is it loaded?” I asked. “Isn’t that dangerous?”

“It’s dangerous to have an unloaded gun in the house,” Dad said. “When you pick this gun up, it better be loaded and you better be ready to use it.”

“I’m six,” I said.

“I’m just saying it’s not a toy.”

“It doesn’t look like a toy,” I said.

“And know . . . if you pick up this gun and point it at someone”—Dad looked at me intensely—“you have to kill them.”

“Couldn’t I just shoot them in the leg or something?”

“No,” Dad explained very analytically, “because now they’re shot and they’re angry, and they’ll have a lot of adrenaline, which can overcome a busted leg, you know?”

It was then that Mom walked in, asking about the broken chair. She looked at me standing across from my dad. And when she saw the gun in his hand she turned whiter.

My dad saw this and smiled. “I was just showing—”

“I knew the girls were going to find the gun.”

“She didn’t find it,” Dad said. “I was just showing it to her.” For some reason this calmed Mom down a little. He continued, “I was just explaining that it’s not a toy.”

“Go play outside, please,” Mom said to me.

“What’s your problem now?” Dad shot back at her.

I circled the block three times, thinking about what a fun, exciting day it had been. And when I came back around the third time, there was Latifa. She was playing hopscotch by herself and I could not have been happier to see her alone and playing a game I knew.

“You want me to play with you?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said, smiling. I took the key from around my neck to use as a marker. I was about to throw it down when Latifa shook her head and motioned to her mother, who was walking out onto the porch above the steps, carefully surveying our interaction. Her mom saw me with the marker in my hand and decided to stay outside. She took a seat in a padded metal chair, watching the two of us carefully.

“Um . . . you better go,” Latifa said apologetically. But I just looked at Latifa, confused. She had a nervous look on her face and I followed it up to her mother, who had her arms folded and her lips pursed at me. When I looked questioningly at her mother, she looked away, avoiding eye contact—her disapproving face said it all. I was to go. As I walked away, the blood rushing to my cheeks, I finally realized what they meant by whitey.

One

I’M IN A CAPPIN’ MOOD

I KNOW DIVORCE is supposed to be hard on kids, but when my parents finally did it, it wasn’t really that hard on me. They were so mismatched that the year before they got divorced, I often wondered if Dad met Mom by mistakenly wandering into a poetry reading thinking it was a Parliament concert. Dad was cool. Mom was Mom. They were both attractive, but other than that, they didn’t really make much sense. Their differences became louder every day. So when my mom didn’t come home one night, my first thought was, “I hope Dad’s new apartment has an elevator!” I was only seven, but I already knew how divorce worked. Dad moved out and got a cool apartment with a pool. We lived with Mom, of course—it was the mid-eighties and moms always got the kids. But we’d visit Dad on weekends, swim in his pool, and he’d buy us lots of stuff to make sure we still loved him. He would be there just to make sure that we were growing up to be cool, going to enough parties and dressing right. There would be two birthdays and two Christmases. And maybe Mom would move to a new neighborhood, and I would have new neighbors who liked me. Plus, if I was lucky, one of them might have a telescope.

But things didn’t quite work out that way. Dad really wanted us with him. And Mom apparently had some “work” to do on herself—which meant she needed to cut her hair and cry a lot. She started dating a Jewish guy in Mensa, who also drove a bus and had “depression.” And, since she worked full-time, and Dad had always taken care of us during the day, they decided Mom should be the weekend dad with the apartment.

The process happened so quickly that I didn’t even get a vote on where I was gonna live. There was supposed to be a judge, like in the movies, who would take me and my sister into his chambers. Then he would clear all of the adults out of the room so no one’s feelings would get hurt, offer us a Werther’s Original, lean back in his chair, and say, “Okay, now level with me. . . . Who do you like better?” At which point I would say, “Mom.” Not because I liked her better, but because I knew I was cool enough for Mom. And I felt that not being quite good enough for Dad might cause problems down the road—like I’d cramp his style and maybe he’d decide to leave me at a party. Of course, I assumed everyone wanted my little sister Anora—she was adorable. But when I asked Mom and Dad about the judge and the missing courtroom battle I was told that that sort of thing was for rich people and that normal people didn’t ask their kids what they wanted.

The terms of the divorce finalized, Dad announced he was giving me an allowance. I had to take care of my sister, meaning quieting her when she got hysterical and keeping her from wandering off in public places. And for that I got a dollar a week, which was totally a fortune because I measured it in Now and Laters. Then my dad promptly got a summer job doing construction to “show that bitch,” which left my sister and me without daily supervision. “Not to worry,” Dad said. “You guys are going to Government Subsidized Charity Club.” Which sounded really awesome—like the Mickey Mouse Club or the Nancy Drew Fan Club.

Okay, the place wasn’t actually called “Government Subsidized Charity Club,” but for now let’s call it that, or GSCC for short. Our first day at GSCC, we all climbed into Dad’s truck and drove down M. L. K

ing, arriving at the side entrance of a building that was clearly used for something else. We walked up a rickety stairway to a side door and entered a dingy vestibule, where a counselor sat at a table picking lead paint off it. She had a clipboard and two jump ropes—which, combined with the two kick balls—brought the total number of toys in the facility up to four. In addition to the lack of toys, the entire place smelled like pee and cigarettes. I would not have been surprised to find out it was used as a low-bottom halfway house the rest of the year, and that every summer they kicked out people named Gimpy Carl and Staph-man McGee to make room for day camp. I peered from the entryway into a main playroom full of kids, and surprise! My sister and I were the only white kids there. I was also, from what I could see, the skinniest kid—in boxing, that’s what they refer to as “shit odds.” It was then I decided that either Dad was cheap or we were just stopping by on the way to the real day camp.

“Well,” Dad said, signing a clipboard and cementing that we were, in fact, in the right place. “Looks like you guys are good to go.” I guess by “good to go,” he meant that we weren’t standing on broken glass. But I smiled weakly, and I think he sensed my apprehension, because he got down on one knee, straightened my overalls, looked me right in the eye, and said, “Just, don’t take any shit,” before walking out the door.

We were then led into the playroom, and other than the counselor who had checked us in, there was not an adult in sight. I quickly got out of the way as two bigger kids threw the red rubber balls at a younger kid’s head—some sort of two-on-one dodgeball. In the far corner there was a group of girls who were probably around nine, but looked like they were about sixteen. They laughed as they looked at a boy four feet away who was sitting on the ground crying. I decided to avoid eye contact and found a pole near the far side of the room to lean against. That’s when I realized—everyone was staring at me.

I'm Down

I'm Down