- Home

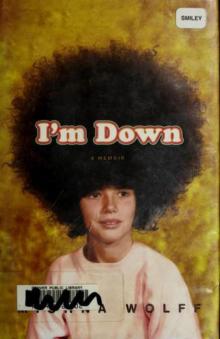

- Mishna Wolff

I'm Down Page 12

I'm Down Read online

Page 12

“Hey, violin!” he said. “Where you going, violin?”

I tapped my chest with my free hand and set the violin down to let him know that if need be, I was ready to go.

But Jason just laughed and said, “Shoot, she ain’t worth the trouble.” And they went back to their dancing and I turned the corner toward my house, still daydreaming about my ski trip.

______

After dinner my sister and I were doing the dishes when the phone rang. Dad answered, and I knew by the way he immediately corrected his posture, he was talking to a woman.

“Mishna, your friend’s mom called,” he said. “Viela.”

“Violet,” I said.

“That’s what I said! Anyway . . .” He paused. “They want to take you skiing this Saturday . . . if you want to go.”

“I do,” I said. “But I think I need some gloves and a hat and I don’t know if I have a warm enough coat.”

“Her mom told me exactly what you need,” he said, scratching his head to remember. “You need some gloves and a hat . . . and what else? Oh, you need a ski coat.”

“When can we get me the stuff?”

“We’ll hook you up by Friday,” he said, looking easy and relaxed. But I was worried, and suddenly, I got a flash of myself in the snow, my ungloved hands turning a shade of purple I had never seen before on human flesh.

“Oh,” Dad said, remembering, “that’s right. You also need lunch money. We’ll just pack you a lunch.” I went back to my vision of the frostbitten hands and added hungry to the mix.

By Friday, I still had nothing to ski in. We didn’t get my gear on Wednesday, because the game was on. We had been over at Jackie’s house again on Thursday. And when I got home on Friday the fellas were over playing dominoes. And I was so concerned about my ski stuff that I wasn’t even excited that Dad’s good friend Delroy was there, which I normally would have been stoked about because he was so smart. Delroy had the Queen’s English, a law degree, and most important, a briefcase. And the fact that he hadn’t passed the bar, after seven years—and three tries—had less to do with the fact that he wasn’t smart and more to do with the fact that he smoked pot every day. Which meant he could totally pass if he really wanted to—and he would become a lawyer as soon as he was done being stoned.

“Hey, genius!” Delroy said as I walked in the door.

Big Lyman was up, which meant he knew everything. “Little Wolff—”

Eldridge corrected him. “It’s lil’ girl Wolff.”

“Little Wolff! Why don’t you come over here and watch me take your daddy to school?”

Dad wasn’t about to take that insult in his own home, and asked in a low voice, “You about ready to go home, Lyman?” Big Lyman was not, and piped down as Dad added, “That’s what I thought.”

“Dad,” I said. “I still need some ski stuff.”

“Ski stuff?” Lyman said, surprised. “You rich or something?”

“Her friends are taking her,” Dad said, as if excusing himself.

“Well,” Reggie said, scratching his chin, “I don’t know what kind of a sport skiing is. The hill does all the work. You just slide. Where’s the ath-let-i-cis-m?”

Almost automatically Dad said, “Did I ever tell you the four-hundred-yard-dash story?”

Lyman spoke up, “I think we all heard about Mishna in the four hundred yard dash.”

Then Delroy chipped in, “I thinks it’s great to ski. Leave her alone.” I was grateful for Delroy’s two cents, but I just needed a coat. I wasn’t up for a whole pro-anti ski debate. Then Delroy added, “I went skiing a few times when I was at Lakeside.”

“You would ski!” Lyman said.

“What’s wrong with skiing?” Delroy asked. “Is it a white sport?” There was silence from Lyman and Reggie Dee. Delroy continued, “You brothers play tennis all the time. That’s a white sport.”

“Well,” Reggie explained, “tennis is a hot-weather sport. You play when it’s hot, and you get hot playing. No brother volunteers to be cold.”

“Oh,” Delroy said, “so, I’m not a real brother. Is that what you’re getting at?”

I was in a hurry for this argument to be over with and said, “Dad’s new girlfriend skis.”

There were looks from all the men at the table. Dad hadn’t told them yet about Jackie, although I couldn’t imagine why.

“Here,” Dad said, handing me ten dollars. “Go to Value Village and get your shit worked out.” I was almost out the door when he said, “And take your sister with you.”

“Hey! Hey! Hey!” Big Lyman added as I headed back out the door with my sister. “Stop by see if Zwena wants to go, too.” So I guessed it was an expedition.

The way my sister walked, stopping to pick up garbage she found interesting, it took us a half hour to Zwena’s and another half hour to get to Value Village, the local neighborhood thrift store. Walking into the store and the glaring fluorescent lights I was reminded again how huge it was—and what mildew smelled like. But Zwena and I loved it there because we could always afford something. It was much better than expensive-ass Salvation Army, where they seemed to think all their junk was made of gold. At Value Village they knew they sold garbage, and it was priced accordingly. And people who shopped there made a joke of pronouncing the village with a French accent, and it was endearingly referred to as “Value Vee-lahge.”

Holding my sister’s hand, I followed Zwena to the kids outerwear where Anora promptly broke free and wedged herself into the middle of a rack of clothes. Zwena found me a green wool hat without too much trouble and it actually had a skier on the tag, so I knew it was the right kind of hat. But the only gloves I could find were bright pink mittens which felt a little young for a fifth-grader. There were only two coats that really fit the bill. One was black, which I liked but not with pink gloves and a green hat. The other one was red and blue, which I also didn’t like with the other colors. I held them both up for Zwena.

“Hmmm,” she said through a head cold, “I think they’re both pretty good. But I don’t know anything about skiing.”

I turned to Anora. “Which one?”

A little head popped out from between faded rayon. “The red one!” she said, smiling.

“You sure?” I asked.

She thought about it and said, “The black one.”

“You’re not helping,” I said as she climbed back into her rack.

“I’m a caterpillar.”

“You are not!” I said. “You’re my sister and you’re crawling on the floor when I took you someplace.”

“Fine,” she said, and popped her head back out. “What are you wearing underneath?” Zwena and I looked at each other stumped.

An old black lady with plastic bifocals was putting some dusty paperbacks on a shelf nearby and Zwena jumped into action asking her, “Excuse me. Do you know anything about skiing?”

“Well . . . Not too terribly much, but what can I help you with, sweetie?”

Anora pointed to me and said, “My sister is going skiing for the first time and she needs to know what you wear under your coat.”

“You’re going skiing? Well, isn’t that exciting.” The lady looked at the red and blue coat. She studied it very carefully and said, “I think I know.” She went over to a rack of girls turtlenecks and picked out a bright red one. Then she put the coat over it on the hanger. They looked great together—very professional.

“That’s it!” I said.

“Oh, yes.” The lady nodded. “You’re gonna look sharp.” I was sure I would, too. We thanked the lady and I counted my items to make sure I had enough money. Zwena did the tax in her head and we scraped through checkout with fourteen cents to spare.

The next day Violet’s mother showed up in their minivan.

I ran out of the house and got into the van and Lilith laughed and said, “None of us could figure out how you were gonna get out of your house.”

I had almost forgotten about the ten-foot drop from the front

door. “There’s a back door,” I said dryly. It was too early for laughing.

We drove to a ski area about an hour away. And while Violet and Lilith headed for the slopes, Violet’s mom brought me to the bunny hill and showed me how to use the rope tow. And I fell, and fell, and fell. A half hour into the day my ski pants were already wet and I felt like I had been beaten with oranges. The one thing I was not, was cold—simply because getting back up with all that gear on, and hiking to where my skis had gone flying off me, required so much energy that I felt like skiing was actually making me old.

After about an hour of this, Lilith and Violet skied by to check on me in my crumpled pile next to Violet’s mom. Their parallel skis skidded to a stop, spraying beautiful ski wake into the air. Their matching one-piece ski outfits were dry as a bone and they didn’t wear hats but rather precious woolen headbands that covered only their ears.

“How is it going?” Lilith said. “Is she skiing yet?”

“Yes,” Violet’s mom said. “She’s looking good.” I had no idea who she was talking about. I was sitting like a pretzel where I had fallen under the rope tow. And I was done skiing. I was just too much of a pussy to tell anyone.

Violet suggested, “Maybe me and Lilith should take her on the lift.”

“Hey, guys!” I said shakily. “Let’s not do anything to put me in danger.”

But once I got on the lift I actually enjoyed skiing for the first time all day—or at least the chairlift part. Apparently there were rides in skiing, like at the fair—but slower so you don’t throw up. And, from the lift-ride, I could see snow covered hillsides and trees—basically a full-on winter wonderland. It was beautiful. And when we arrived at the little house at the top of the hill, and I patiently waited for them to stop the lift so that I could get off. But they didn’t stop the lift and then I noticed Violet skiing off the lift and calling to me, “Come on!”

I thought, Surely she’s not asking me to get out of my seat while the ride is still in motion. I didn’t think anyone could possibly expect that from me.

No sooner had I thought that, than an alarm went off and there was shouting and the man operating it came running out of the little house waving his arms and screaming, “Get off! Get off! What’s wrong with you?”

And I answered honestly, “I dunno.”

I arrived home that evening never wanting to ski again. Dad and Anora were out and I peeled off my wet socks and lay down on the brown vinyl couch. I felt good for the first time all day. I would sleep until the aches and the humiliation were gone.

The next thing I knew Jackie’s voice said sweetly, “Look. Poor thing is all tuckered out.” And I hurled myself out of sleep, only now realizing my cheek was soldered to the couch by drool. I wiped my cheek and looked up. Jackie, sweet Jackie. I was even happy to see Dad and Anora. Then I noticed Zaid frozen in the entryway gaping at the unfinished cement landing and the picture of black Jesus in the dining room.

“Hey, skier!” Dad said excitedly. “How was the ski trip?”

It was awful, so I said, “It was awesome!”

“Wow,” Anora said. “I want to ski.”

“It’s pretty complicated,” I said.

“Well,” Dad said. “You can teach us a thing or two next weekend.”

What the hell is he talking about?

“We are all gonna go skiing . . . I decided,” he said. “As a family. With Jackie and Zaid.”

Jackie cooed, “Oh, John. You’re gonna be a great skier. I just know it. I’ll show you some stuff, and by the end of the day you’ll be beating me and Zaid.”

Dad smiled at the idea and said, “That’s probably true.”

The next week I set out with my family to the exact same mountain I had been on the week before—knowing full well that the odds of running into people I knew was a solid 97 percent. Jackie was behind us in her car because Dad insisted on driving us in the boat. Which was super, because the holes in the floor allowed us to monitor the climate change as we drove into the mountains. Anora and I watched through the missing floor as we passed from cold draft, to really cold draft, to snow. And when we skidded onto the shoulder, that was the first we heard that Dad didn’t exactly have snow tires.

“Don’t worry,” Dad said. “I lived on the East Coast. I know exactly how to drive in this shit.”

The rest of the way up, I sat in the back of the boat, was going five miles per hour and swerving all over the place, as speedsters in their four-wheel-drive vehicles honked past us. And, just to make sure none of my friends could possibly see me from their passing vehicles, I got as low in my seat as I could.

When we got into the parking lot of the ski area, I made sure the coast was clear before getting out. We needed to get our rentals and our lift tickets, which left me chained to Dad and my sister for an hour in the very busy lodge that could be home to any number of my schoolmates. This was a melding of worlds I had not bargained for. Jackie and Zaid looked great, but my father was wearing blue jeans, work gloves, a long-shoreman’s hat, and a coat about a size too small. He looked like a ski lumberjack. And my sister had on a metallic Value Village one-piece that was about a decade out of style. As we walked the halls of the lodge collecting the things we needed to start our day, I became more and more terrified we would run into someone I knew. Sure enough, we were just leaving through the rental shop when I ran into Violet, her mom, and her sister. Violet waddled up to me in her ski boots.

“Oh, awesome,” Violet said. “I’m about to meet Lilith on Bonanza. Come with me.” But when I looked at Dad he gave me the look.

“I’m gonna ski with my family,” I said. Violet gave my family the head-to-toe once-over: Jackie, Zaid, the ski lumberjack, Anora the disco skier, and me. We were like nothing they had ever seen on the mountain. While Violet’s mother started chatting with Dad and Jackie, I took the opportunity to lean against the lockers and look like I wasn’t with them.

We hit the slopes, and Zaid went off by himself, having had just about enough of us already. I was actually a little disappointed he didn’t want to spend some time laughing while I fell. My sister, Dad, and I went to the rope tow with Jackie. And I had to admit it, Dad was a bit of a natural. In fact, so was Anora. So much so, we were off the rope tow and onto the lift after about two runs.

At lunch, Jackie pulled out a homemade picnic and I decided to set aside the embarrassment of sitting with my family and pay homage to the glory of food. I was famished, and Jackie was such a good cook—she had made fried chicken and macaroni salad, and she even packed juice boxes for us, just like a mom.

As we finished I saw Violet again and got excited. She was sitting across the room with Lilith and Lilith’s mom and sister. Violet’s mom was standing in line with Violet’s little sister getting some drinks. And when I finished my food, Dad said smiling, “Why don’t you go over and hang with your friends?”

The next day, I felt confident enough in my skiing to talk about it a little at school. I went over to Violet’s desk before PE and brought up some of the runs we had been on in front of Catrina Calder, who I knew also skied. Catrina, of course, joined in the conversation and we chatted a little about the conditions as we lined up and headed out the door to the gym. I was a skier, and I stood next to Gretchen who also skied and recounted my Saturday until we got into PE and sat down. There was always a lot of speculation about what we would be doing in gym and I was hoping for Wiffle Ball, because I could use the time on the bench to talk about skiing more. It was then Mr. Tully, our PE teacher, announced we would be break-dancing. My class of twenty-one white kids and six “others” went crazy with excitement. I, on the other hand, was queasy. I wasn’t sure which was disturbing me more: the fact that Mr. Tully was trying to “hip up” gym class or that he was dressed like an extra from Roller Boogie.

He faced a class of elementary school students in a pair of shorts so short that the only reason his junk stayed in was because they were also skintight. His polyester shirt was half unbuttoned

to show off his insanely hairy chest. His upper lip disappeared into his well-combed mustache as he described the break-dancing “moves” we would be working on. He almost drooled on himself as he pointed to three large poster boards, with step-by-step instructions on how to do the six-step, the backspin, and the worm. I could tell by his excitement that he was sure he was blowing our young minds the only way a PE teacher can—by bringing the street into the curriculum.

Mr. Tully put Run-DMC on the sound system, and I watched in shock and horror as Chaim, a chubby Jewish kid moved along the gym in a motion that can best be described as floor-humping. I walked up to Donald, who was waiting for his turn to try the windmill.

“Hey, Donald,” I said.

“Hi,” he said cautiously.

“So, I went skiing this weekend.”

“Oh, it’s my turn!” he said excitedly. Then he took something out of his coat pocket and put it in my hand. “Will you hold my mealworm while I go, I don’t want it to get crushed.”

“Okay,” I said, not feeling like I had a choice.

But it was all too insane to me. My class of preppy intellectuals had break-dancing fever, and they were trying to act like little Jasons and Tres as they did their pop-locks and freezes. When it was my turn, I didn’t want to do it; I wanted to brag about skiing. I waited for Donald to finish and pushed his mealworm back into his hand. Then I asked Mr. Tully for the bathroom pass and didn’t come back until just before the class bell rang. Instead, I locked myself in a bathroom stall and counted square tiles on the floor. Then my fingers skied down the large white sink and defied gravity by skiing back up.

After PE we had lunch, which meant more opportunities to talk about skiing with anyone who would listen. I tried to strike up a conversation with Chaim, who was ahead of me in line.

“Hey,” I said, “I went skiing this weekend. I took a couple of runs down Bonanza.”

I'm Down

I'm Down